We all have biases. They’re our brain’s way of reducing the energy it takes to deal with the terabytes of information thrown at us every day. We connect the dots, fill in the gaps with stuff we already think we know, to then act as fast as we can. Great for avoiding sabre-tooth tigers. Not great for solving customers’ problems, devising product strategies, and making complex decisions. Unfortunately, just knowing about biases won’t make them go away. We have to design our interactions to expose and avoid them as best we can.

I run a fair few offsites and strategy and planning sessions, and I often see some familiar cognitive biases in action. I thought it would helpful to look at cognitive bias through this lens.

So, here are 5 cognitive bias examples to watch out for, and some ideas for what to do about them — whether preparing for a meeting, or anytime.

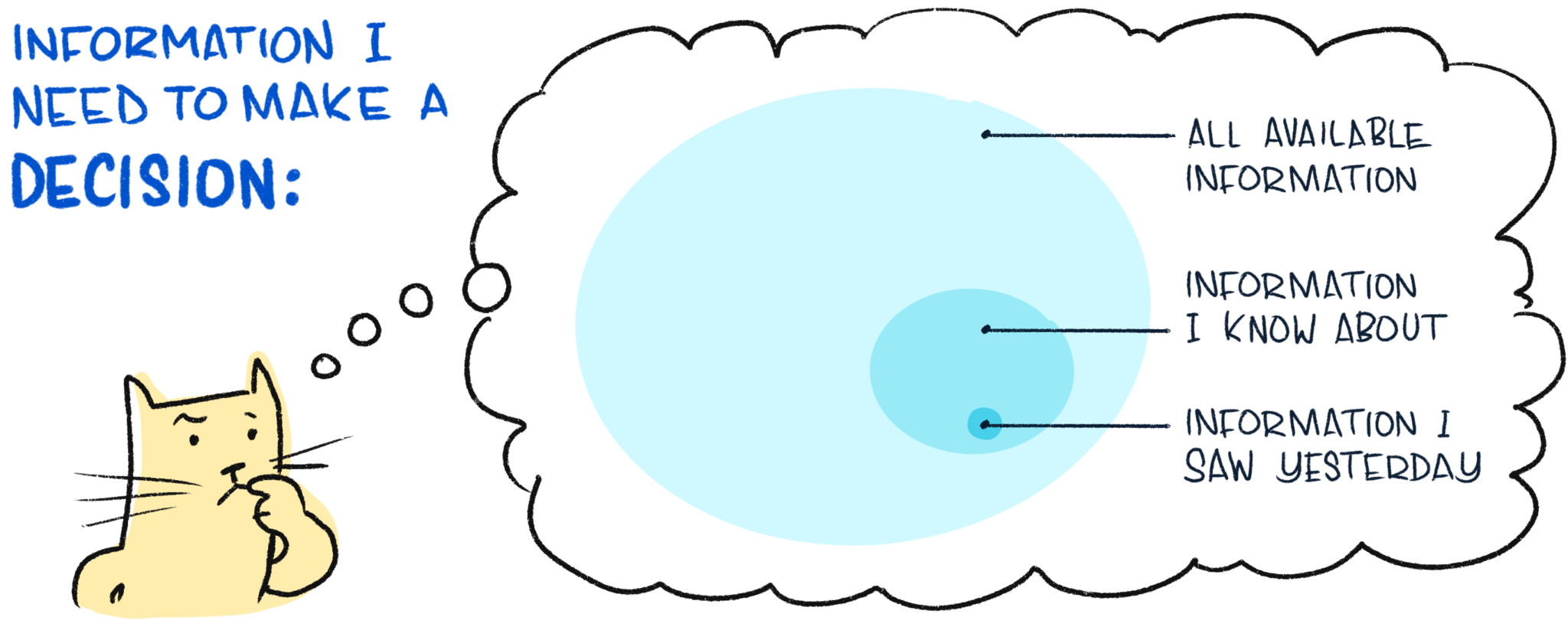

1. Availability bias

Let’s say you have an offsite coming up. Maybe you’re the one organising it and building the agenda. What comes to mind when you think about pre-work needed?

We’re more likely to notice things – and spend more time thinking and talking about things – that are related to what’s recently been encountered. This is the availability bias in action: we seem to notice something more often once we’ve seen it the first time. It gets worse, though: we can’t help but assume that if something (e.g. idea, risk, solution, etc) can be recalled, it must be more important than any other ideas/risks/solutions which are not as readily recalled.

This is a killer during the start of an offsite, where everyone’s meant to have a shared comprehensive understanding of the current situation. It also constrains brainstorming or ideating/prioritisation activities, because it starves any alternate or emergent ideas of oxygen while fixating on the first idea.

Here are some ways to avoid the availability bias:

- Fight the peak-end rule and confirmation bias when doing any pre-work, or delegating pre-work for your session. Don’t just use the most recent information available, the most referenced information, and/or the information you feel most strongly about, but do the extra homework (and share the load with others) to gather information across a longer period of time, or from a greater range of sources.

- Presentations at the beginning can falsely constrain outcomes. If your offsite is starting with one or more people presenting information, check in with them first to see if what they present is going to bias everyone else toward a certain information source or outcome.

- Don’t just invite the usual suspects to the offsite. Embrace the fact that everyone present will exhibit the availability bias, and encourage a better outcome by inviting a more diverse range of people, memories and thinking.

- Our brains love free association. If you’re doing any brainstorming or ideation for strategic options, help people fight the tide of cue-dependent forgetting, and help them get out of the regular thinking rut by having a wide variety of photos and other visual cues up on the wall, to stimulate ideas by association (the more random the better).

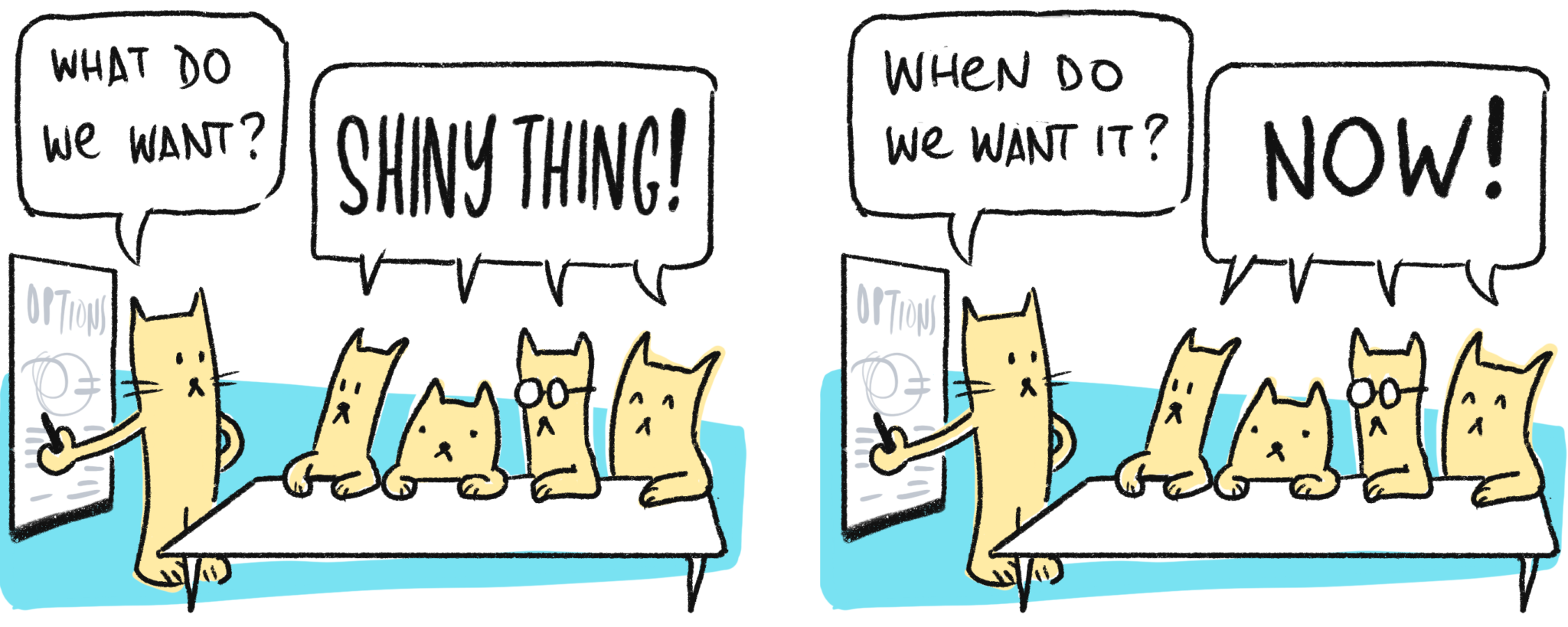

2. Hyperbolic discounting bias

Okay, so your offsite was going well, but now there’s tension in the air. Your group has reached that dreaded point of ‘analysis paralysis’ and ‘ship to learn’. It’s that moment in the conversation where we realise that we’re never going to have enough information to be 100% confident with our understanding of a complex situation, or in making a complex decision. So… we should just make a call, move on, and learn. But we’re still not clear on what that actually means, what success would be, and what action we can take… but let’s just do something so that at least we’re moving.

You feelin’ it?

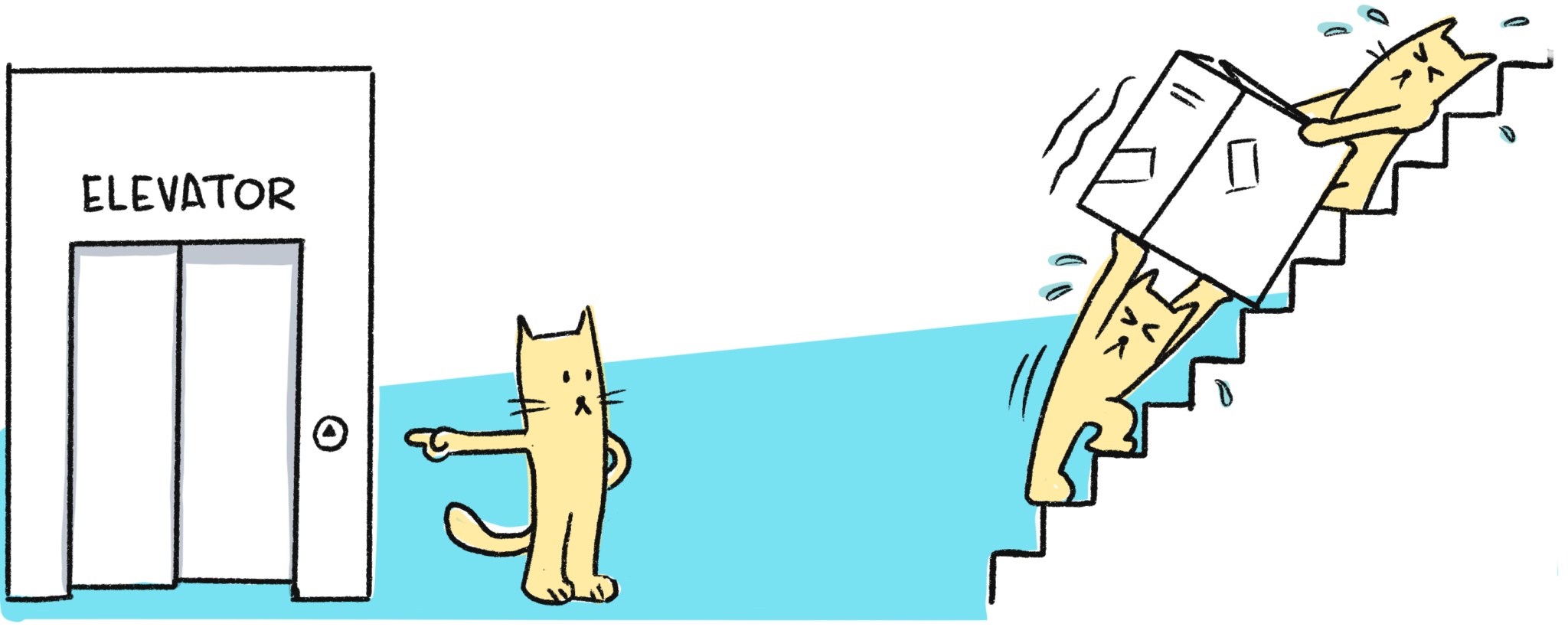

That restless urge for action for the sake of it is the hyperbolic discounting bias. We generally prefer to receive a reward that arrives sooner rather than later, and we discount the value of the later reward, the further it is away. Crazy, right? Shiny tangible thing now, ambiguous-but-more-valuable thing later.

We all know this, but it’s what happens next in the discussion that determines whether the offsite is a mediocre collective shrug, or something truly extraordinary.

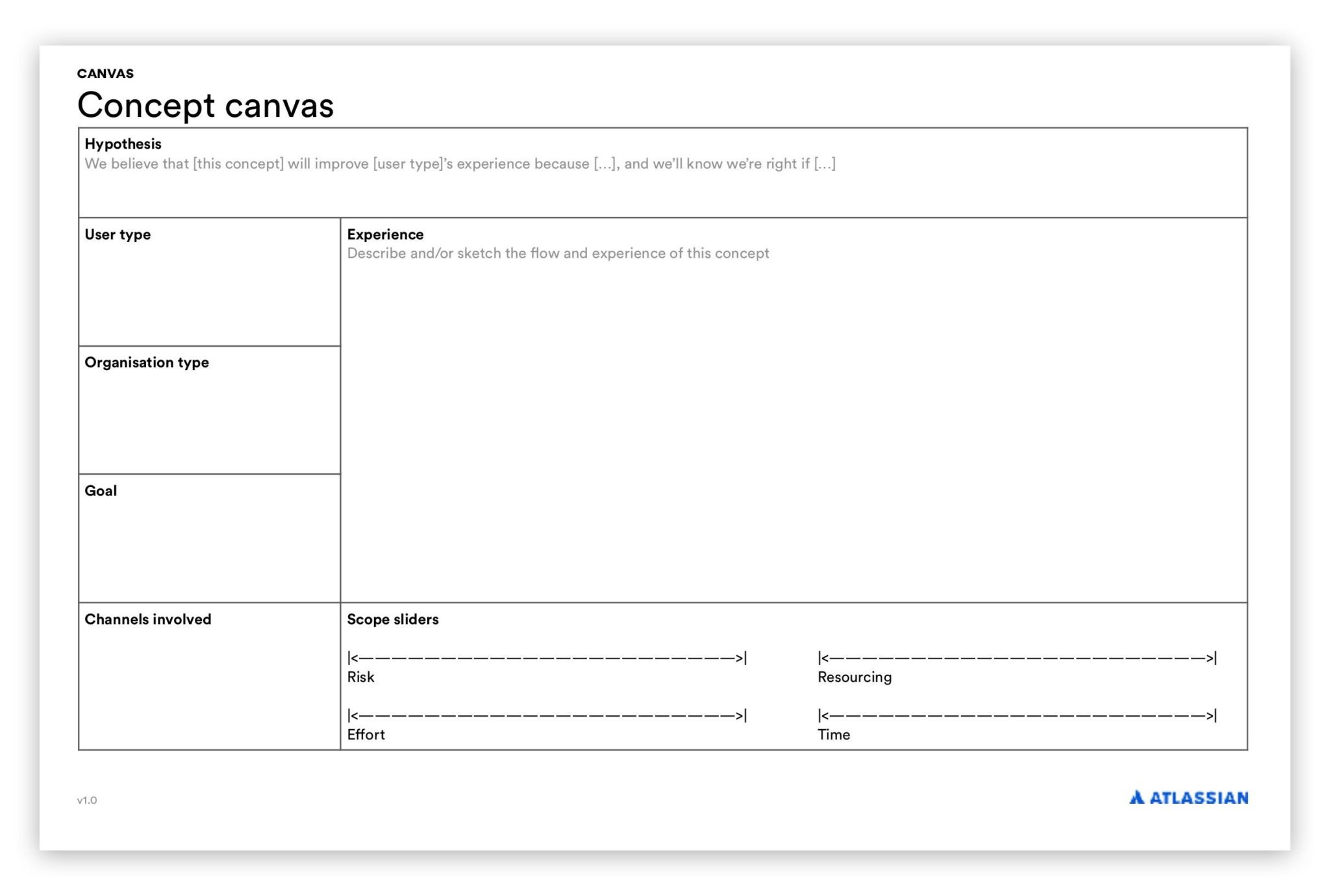

Here are some things to try:

- Ask your group: “We seem to be really anchored into [doing the short-term thing]. Thought experiment: how would we argue to do the [long-term thing] instead?”

- Write out each strategic option/objective/idea on a Concept Canvas. This helps everyone to objectively evaluate options apples-to-apples by shaping each option in the same way, with the same sliders.

- Keep your group honest by helping them to compare their chosen option with the strategic goal they’re aiming for: will this option get them to that goal? If not, what will? What are they uncertain about, and what would help with that uncertainty?

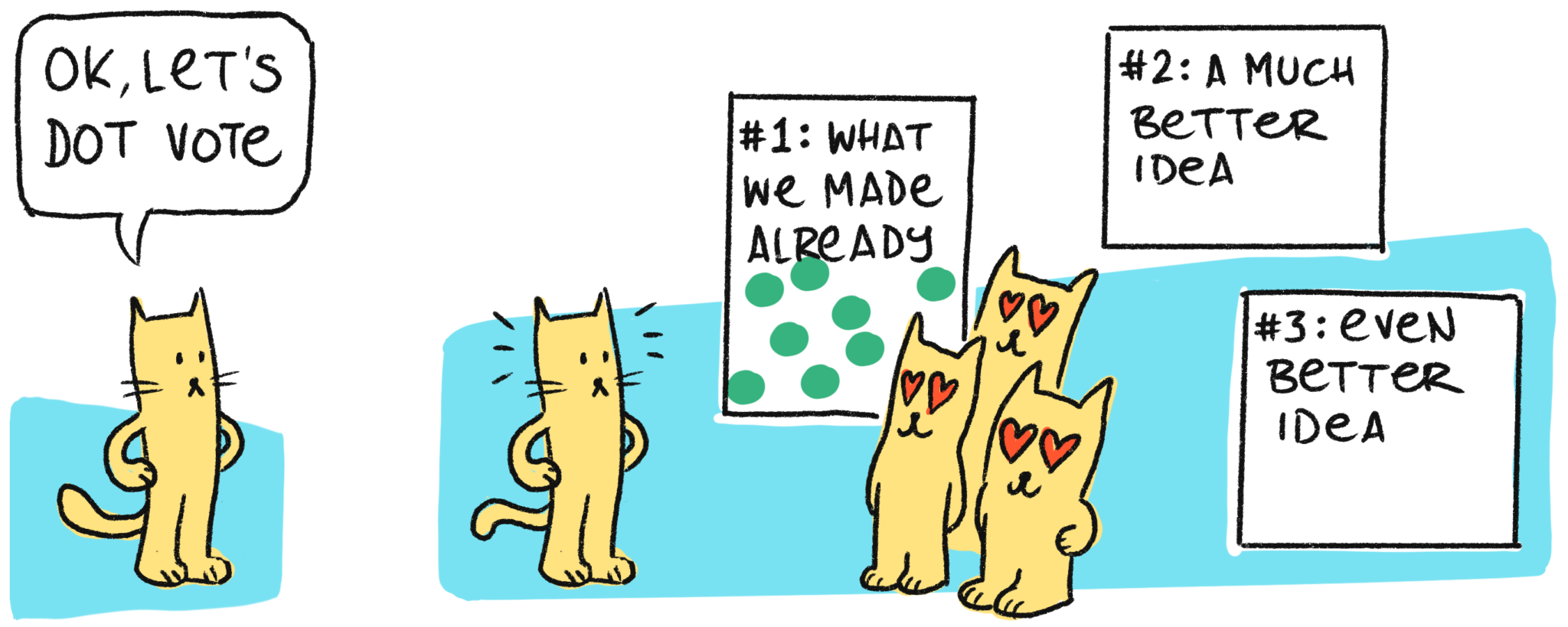

3. Modal bias

Now it’s time to come up with as many ideas as possible! But watch out: entering stage left is Modal bias. Modal bias is the automatic assumption that our own idea or approach is best. Its close cousins are anchoring bias, where any decision we make is heavily influenced by comparing various options to the first option we know of (in this case our own idea), and the Ikea effect and Not Invented Here, where we place disproportionately high value on things we have (partially) created.

And if one person favouring one idea isn’t enough to deal with, sooner or later the Bandwagon Effect kicks in, where we are more likely to agree with an idea if lots of other people already believe it (i.e. groupthink).

Here are a few ideas to help inoculate against modal bias and its garrulous cousins:

- Ask everyone to willfully suspend judgement long enough to thoroughly consider suggestions and perspectives of others, as well as cold hard facts and data. Crazy ideas still lead to useful ideas.

- If you do have anyone who still clutches relentlessly to their idea, get them to argue for others’ ideas instead, to help them see others’ perspectives.

- Don’t just discuss different options in a subjective abstract fashion; road-test them under a wide range of scenarios. Think of this as usability testing for options.

4. Sunk cost fallacy

It looks like you have a pretty good strategic option on the table, but no-one’s going near it. Wait, why? Because doing that option means stopping what we’ve been doing… and that makes people really uncomfortable. Here’s where the sunk cost fallacy looms large, and sinks its Dementor-like talons into everyone’s brains. I see this happen a lot. We can’t help but stick with things that we’ve already invested time and energy in, because of what it’s cost us already. Even if we come across more and more reasons to change, or give it up.

Oh sure, you’ll hear some very responsible-sounding reasons for not cutting the cord and doing the new strategic option instead. We’ve come too far. We don’t have the data to prove otherwise. It’s too late. Our reputation will take a hit if we roll back now. People might dig in even harder. Or they might try bikeshedding on trivial issues, to distract from a tough decision. But it’s still the voice of the Loss Aversion Dementor, not the voice of objectivity.

If you feel the cold clammy grasp of this bias in the room, try asking these questions:

- “If we hadn’t already invested in [this existing option/course of action], would we still do so now? What would we say to a colleague if they were in the same situation?”

- “I think we might be bikeshedding here. Thought experiment: say I wave my magic wand and that [trivial issue] is now completely fixed. What would we do now?”

- “What are the actual risks/effects of doing this new option? How do they compare to the risks/effects of the current option? Do some of us see it as more risky than others? Why?”

5. Bystander Apathy

You’re now at the end of your offsite! But maybe you all need to make a decision, but the group can’t quite get there? Or you’re trying to capture next steps, and the session ends with a list of tasks but no names against them? That’s Bystander Apathy: the more people there are available to do something, the less responsibility each person feels to do anything.

If there is a decision to be made, a group can and should make a call on who makes the ultimate decision, but there must be one person to take the lead in making the decision. Of course this isn’t a ticket to autocracy and HiPPOs; that one person should still make the decision based on inputs from various people. I know you might not agree. That’s fair enough. One approach might work for one group but not another. Whatever. But make the decision, or be real about why your group can’t.

As a facilitator, try to settle ahead of time which individual makes which decision. How that individual needs to make it, and what information she needs, is actually a great start to the agenda and structure of your session. Also, when it comes to ‘next steps’ time, the best thing to do is not let people go until there is a specific name against each of those next steps, for individual accountability.

I hope you found this helpful. It is hard work fighting our lizard brains all the time, but it’s totally worth putting in this extra effort, for better ideas, more objective critique, and better decisions. If nothing else, try these:

- Define clear criteria to objectively evaluate each option, and use them consistently. Using the same standards to evaluate all options can reduce bias.

- Road-test different options, give them enough time and oxygen to see how they play out.

- Be mindful of who you have in your strategy session. Who’s included and who’s excluded?

- If you see something, say something. If you’re getting the vibe of a particular bias, call it out.