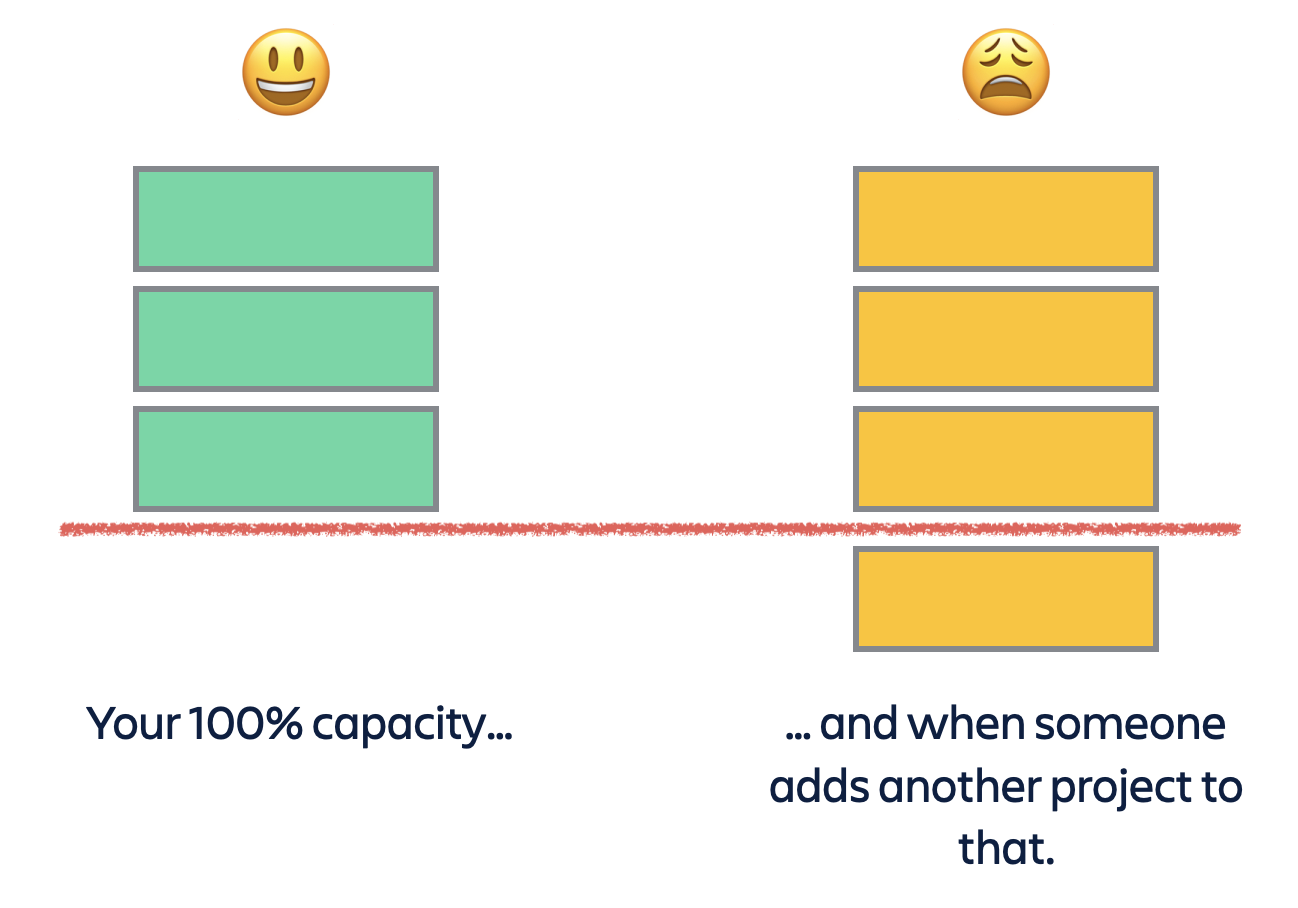

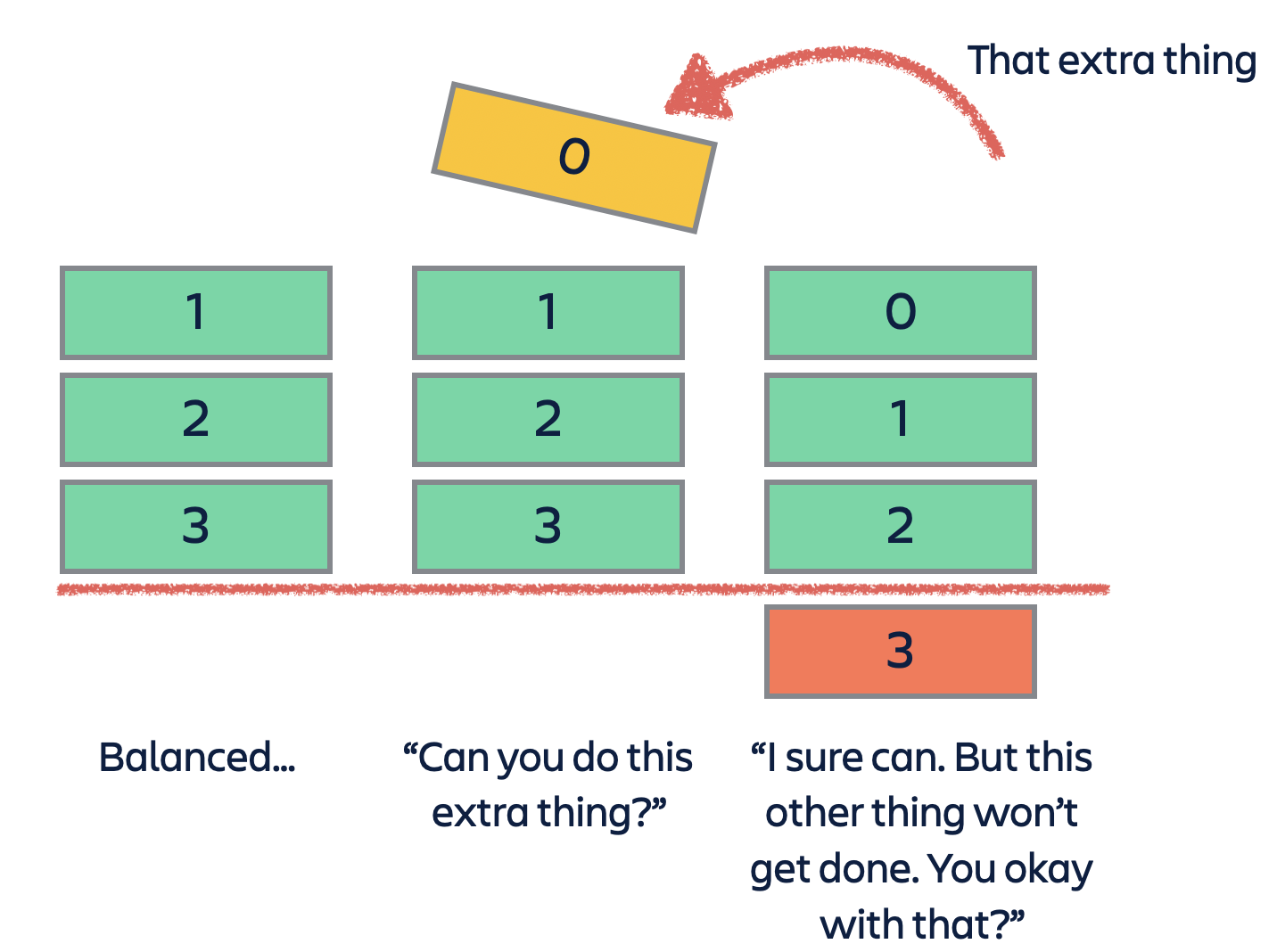

Here’s a crash course in how to spread yourself too thin. Your workload is perfectly balanced. You have exactly the right number of projects and activities on your plate to fill out your week and deliver with a high degree of quality. Hooray! Then, in your 1-on-1 with your manager, they ask you to drive (or look after, or contribute to) an Extra Thing™.

Naturally, you agree. Maybe because you’re really excited about the work, maybe because you don’t feel like you have a choice. Either way, this pushes you into that territory of being “above capacity.” Or, to use an extremely simplified graphic:

Of course, what happens next is that you work harder and/or longer to deliver on those extra expectations. Chances are, the quality of what you deliver drops due to being overworked. And maybe at some point (ok: for sure at some point), the Extra Thing™ turns out to be bigger than expected. So it’s not just one week that you’re above capacity. It turns into a month or more. And even if it was just one week, that’s still a situation worth avoiding.

Why it feels impossible to say no

Many times in my career, I’ve heard this sentence: “You have to get better at saying no!” Or at all-hands meetings, the more inclusive “We have to get better at saying no!” – often followed by the concession “I know that’s not easy.”

But we all know it’s not that simple. It’s empty advice because it ignores the context of the new thing you’re being asked to do.

- The new thing could be really sensible and might actually be the most important thing you could be doing right now. I see this as the best possible scenario.

- Remember that 1-on-1 where you were asked to say no more often? You might find out that this directive, ummm … doesn’t apply to this new thing your manager is asking you to do. *ahem* (Full disclosure: I’ve totally been that manager once or twice.)

- You might worry about how a “no” reflects on you as a person, and what people (especially your manager) might think of you afterward.

- You might also wonder whether saying no will come back to bite you into the backside. To use an example from my world, a new product feature might be criticized for lack of design input. Yet the fact that you had to say no for capacity reasons has gotten lost.

So basically, you can’t just say no.

Here’s a way to say yes

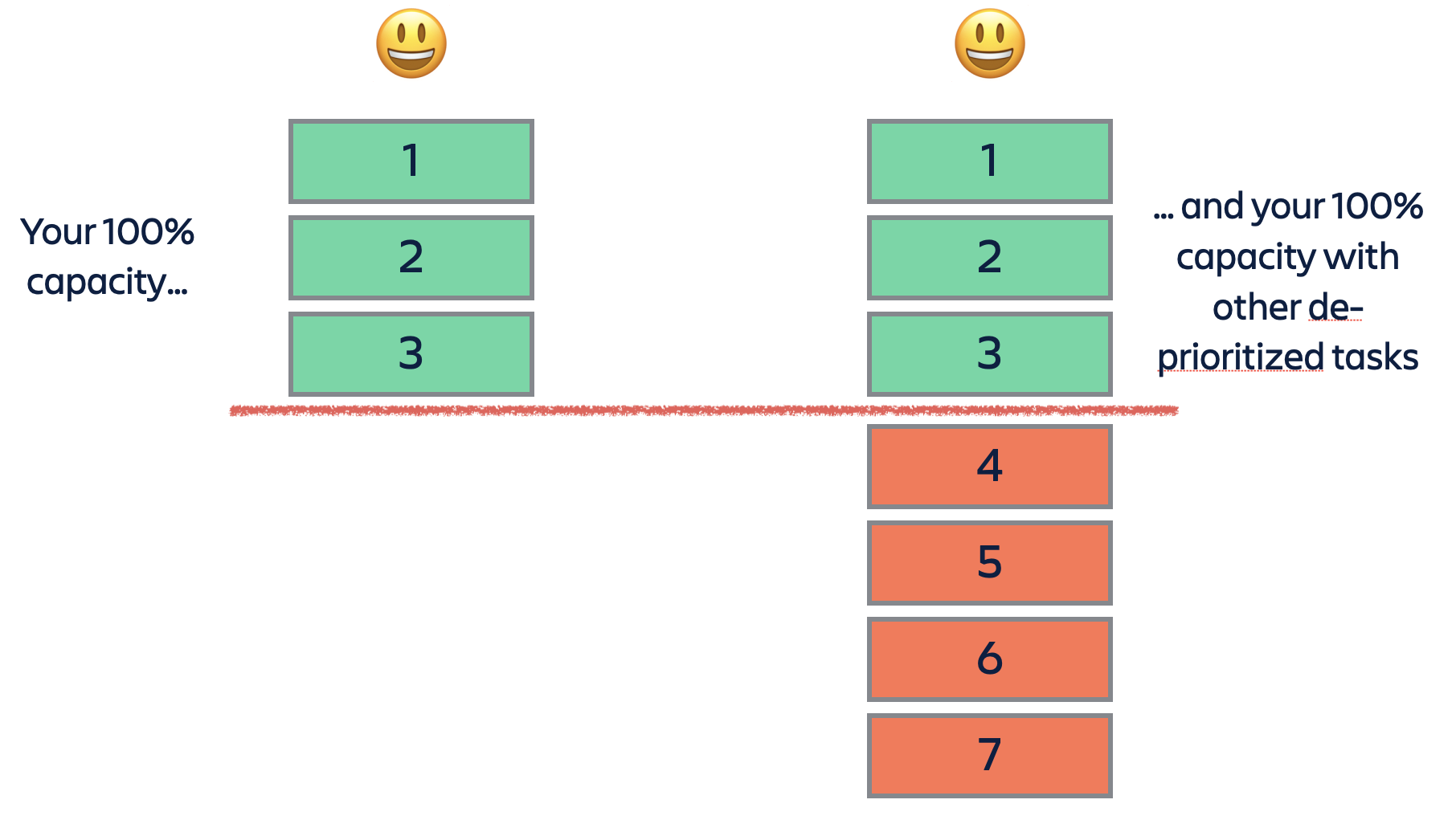

Let’s go back to the scenario above, but rewind the tape and try it again. Here you are, with the perfectly prioritised tasks that you’re currently working on:

Wait a sec! Why have those first three blocks stayed green? Why are you still smiling? What was the magic trick you just pulled there?!

So. Somebody (your manager, a peer, your manager’s manager) comes to you and says, “Can you do this Extra Thing™ for me?” And instead of struggling to get out of it, you might say, “Of course. What would you like me to de-prioritise to make space for this?” Or, if your priorities are quite clear to you, then you would respond with, “Of course. But please be aware that I will have to drop <your lowest priority item> and come back to it later.”

Now, the person asking you to do this new thing may not the same person who will suffer because one of your projects moved below the line. So don’t be shy about explaining the repercussions to them. If they are still the person who should make this call, then fine. If not, ask them to clear this with whomever is being affected negatively. Sometimes that will give them enough pause to retract the request entirely or rethink their need-by date.

Notes on prioritisation and matrixed organisations

Notice that I’m not going into how to make good decisions about priorities. That’s a whole separate article. Probably an eight-part series, actually. Although, now that we’re on the subject, I’ll share a few thoughts. Prioritisation is about two things: how important something is and how urgent it is. Other aspects to consider include:

- Who is asking?

- What’s it for? Which project or goal is this serving?

- How much focus does this work require? Or, how easy is it for me to do this?

- How much do I personally want to do this? (Think: personal growth, personal goals, fun, etc.)

- … and probably a dozen other questions you could ask yourself.

If you’re working within a straightforward organisational structure, there’s usually some wiggle room based on these factors. But if, like me, you work in a matrixed organisation – where you’re accountable to both your business unit (in my case, Atlassian Marketplace) and your functional team (for me, Design) – negotiating priorities comes with an extra degree of complexity. And that is something we should go into in this piece.

The more teams you work for, the higher the chance you’re going to run into a situation where the things you’re working on are the #1 priorities for each team. The conversation about which of these “#1 priorities” should be bumped to the #2 spot is hard. But the conflict needs to be addressed openly so you have a fighting chance at finding the right solution. That might be time boxing your participation in the Extra Thing™, shifting the work over to a teammate (which, of course, means they’ll now be in the capacity hot-seat, but maybe it’ll be easier for them to resolve), moving the due date out, or accepting lower quality work.

Advantages of discussing priorities vs. just saying no

There are several reasons why this approach will (in theory) lead to different results.

- For you, the impact is direct: your workload doesn’t exceed your capacity. Yes, you might have to shift priorities and suddenly work on something new, but you’re not spread too thin.

- The person asking you to do this extra thing gets an insight into what you’re already doing. This is really important. It’s difficult to keep track of all the things everybody is doing. And that’s not even taking into account how challenging it is to be aware of everyone’s obligations to different parts of the org (like your business unit vs. your functional org), weigh one OKR against another, etc. The more transparent you are about why the various things on your plate have the priorities you prescribe to them, the more fruitful the re-prioritisation discussion will be.

- The person asking you understands the price of the Extra Thing™. Namely, they (or more broadly, the organisation) won’t get the other thing that now falls below the line. It may be easier for other people to understand your priorities when the calculation is based on cost/benefit.

I daresay that in the majority of cases, someone ending up with way too much on their plate can ultimately be traced back to one or both parties having incomplete information. This is a good reminder to have a running dialogue with your manager (and anyone else you’re accountable to) to make sure you’re aligned on priorities. Also, to align expectations around what kind of workload someone at your level should be able to handle. Conversations like these present an opportunity to share more details about the work already on your plate and why a new task might push something else off the edge.

Before I go, let’s make things spicy

I don’t mean to antagonise anyone. And I’ve certainly made my share of mistakes, both as the requestor and the requestee. So please, consider these thought exercises and/or conversation starters.

Managers should lead the trade-off discussions 🌶

One of the key parts of being a people leader is taking the time to invest in and protect your team. That means frequent prioritisation, supporting tradeoffs, and going up the leadership chain to communicate what your team won’t do. As such, we managers should be asking: “If you do X, what do you have to drop to keep your work output on a healthy level?” I humbly admit that I have sometimes forgotten this. And maybe others have, too. I don’t think this is very spicy, I wouldn’t expect a lot of push-back.

We tend to over-prioritise tasks we feel closer to 🌶🌶

As a designer, I sometimes place a (potentially unreasonable) high level of importance on design-related tasks. Meanwhile, the business unit I work for actually needs me to do something else that’s not-super-design-related more urgently, like be part of the hiring team for an open position.

This is usually another case of incomplete information. Depending on the size of one’s business unit, it can be difficult to keep track of all the things the business needs to be successful. One might be less familiar with those, and more familiar with domain-specific tasks. It’s a normal bias, therefore, to emphasise your own tasks, because you feel more confident about them.

Please also do not underestimate the pressure a matrixed org can put on both individual contributors and managers. We’re all embedded in our business units, but also part of our functional departments. I’ve found it very difficult at times to get the balance right.

Working from home in the era of COVID may have moved our capacity bar 🌶🌶🌶

This one varies from person to person. For me, since we started working from home, I need to work longer to deliver the same amount. It’s an accumulation of a hundred tiny little reasons. So my capacity is effectively lower now than it was before. You don’t see this point addressed all too often, but very recently, conversations around this have started up, for which I’m grateful.

If you feel you’re affected in a similar way, please make sure to have a candid conversation with your manager. Because self-care .

Sometimes it’s best to let the silence stretch out 🌶🌶🌶🌶🌶🌶🌶🌶🌶

There’s one situation where you only have yourself to thank for being over capacity, and that’s when you volunteer to take on a task. Obviously, don’t just stop volunteering altogether! But before you put your hand up, consider what this means for your “above the line” projects. And if the silence after a call for volunteers gets too awkward for you to handle, then maybe raise your hand and say, “I can do this, but you have to help me take something else off my plate.”

Spiciness aside, I can only speak from my experience as a designer and design manager. In these roles, it’s very common for me to get tasked with new things that I didn’t foresee. It’s a mix of:

- Being in a matrixed organisation: The business unit wants me to do something but the design org wants me to do something else. These two units plan at different times and in different ways.

- Discovering new information: Something I worked on yields an insight that we didn’t have before, requiring new (that is, extra) attention, which I didn’t predict or plan for.

- People manager issues: The various stages of hiring interviews, responding to issues affecting my team members, re-orgs in the company … all of those need little actions and activities and are difficult to plan for.

I think it’s a fairly accepted part of our roles that we need to deal with new circumstances and tasks as they present themselves, and I don’t think that’s a negative thing. Unless, of course, they only ever get added on top of the things you already had on your plate. In which case, please re-read this article 😁