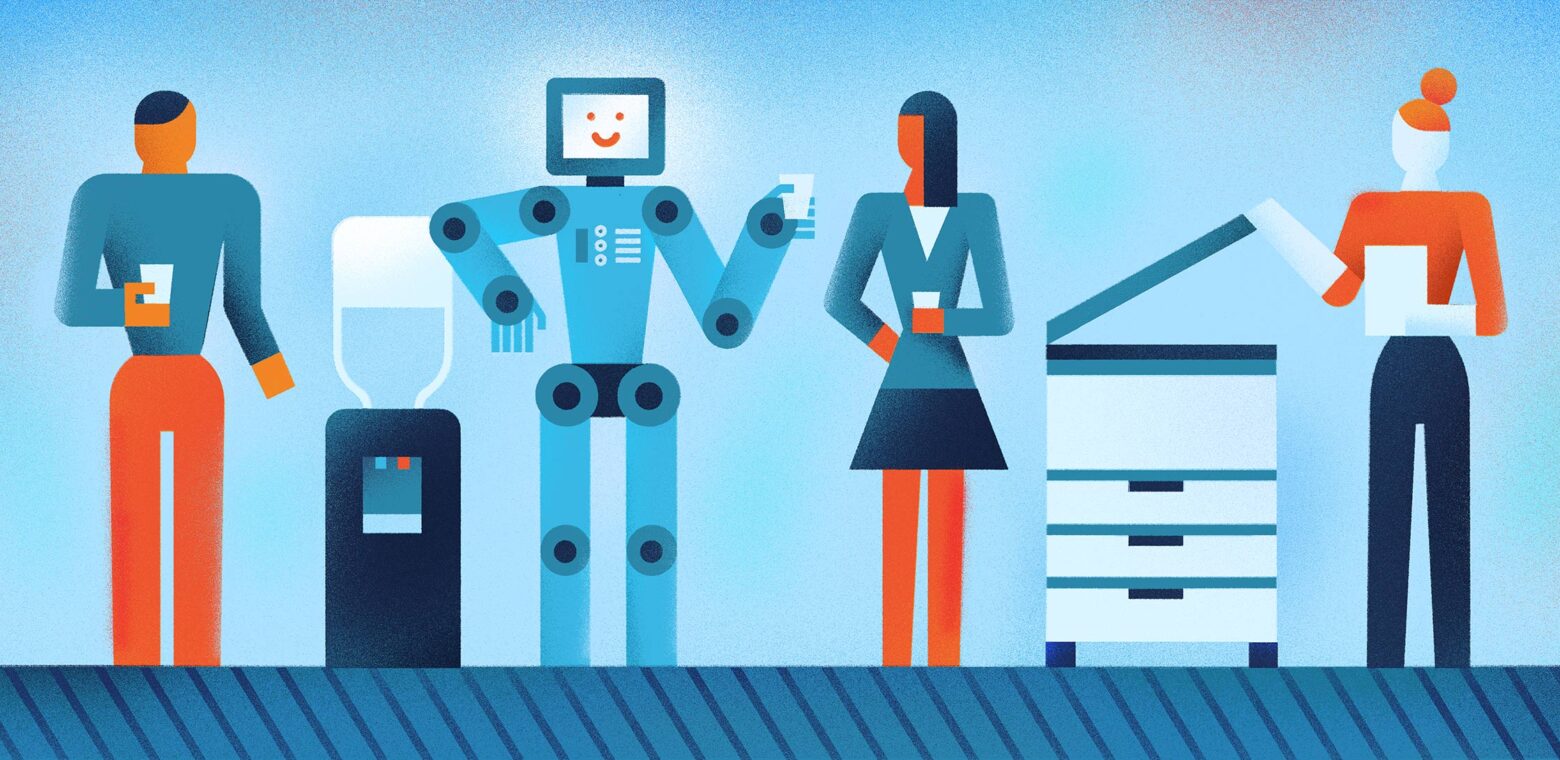

It’s time to make peace with the bots

In the face of AI disruption, teams that embrace a growth mindset will fare better than those who cling to the status quo.

Seemingly overnight, Artificial Intelligence (AI) has become the subject of a whole lot of buzz and speculation, thanks in large part to text- and image-generating bots like OpenAI’s ChatGPT and DALL-E. These emergent tools are already disrupting knowledge-work jobs that, only a decade ago, were predicted to remain “safe” from technological takeover. Although AI didn’t write this article, there may be a not-so-distant future in which many of us consume bot-crafted content without batting an eye.

Whether or not AI is coming for your job, there’s no question that a bot-driven labor shakeup is on the horizon. As has always been the case with technological advancement, from the printing press to the world wide web, workers and organizations will have to be adaptive to remain competitive.

Expectations vs. reality

Researchers have long considered the impact of automation on jobs. But their forecast has changed radically, and relatively fast.

Take, for instance, this 2013 paper by Oxford researchers on the future of work. Its authors determined that jobs based around repetitive, easily replicable tasks were most likely to be replaced by automation, listing “telemarketer,” “dishwasher,” and “court clerk” as examples of particularly at-risk roles. On the other hand, jobs based around “perception and manipulation tasks, creative intelligence tasks, and social intelligence tasks” were deemed by the researchers to be the least susceptible to automation.

A more recent study from McKinsey & Company similarly predicted that, of an estimated 800 million global workers that would be replaced by automation by 2030, the overwhelming majority would be in lower-wage, lower-skill fields. In other words: specialized, ideas-driven jobs were safe. Knowledge workers could breathe a sigh of relief.

But the rise of generative AI – specifically, tools that can make high-quality art and written content from a simple prompt – already suggests otherwise. And some researchers saw this coming.

A 2019 paper from the Brookings Institution posited that, contrary to other predictions, “better-paid, better-educated” workers would have the most exposure to AI – and, by extension, could even be most at threat of becoming redundant as these high-tech tools became more widely available. That’s because AI excels at replicating the types of tasks we typically associate with creativity or specialized knowledge. It involves “programming computers to do things which – if done by humans – would be said to require “intelligence,” whether it be planning, learning, reasoning, problem-solving, perception, or prediction,” the authors wrote. Other researchers may have over-indexed on the necessity of human input in certain jobs that involve these processes.

“A lot of writing is functional and formulaic,” says Tal Linzen, the director of New York University’s Computation and Psycholinguistics Lab and a leading researcher in computational language applications. “I don’t think it’s particularly important to have sentences in legal contracts or user manuals be novel and aesthetically appealing, for instance. They just need to convey the right information.”

But the “right information” will still need to be verified by humans with the qualifications to do so. Continuing the example of legal contracts, Linzen predicts the following scenario: “We might end up needing fewer people who put together new legal contracts by copying and pasting text from other contracts, but we’ll still need a lawyer to supervise the process and make sure the AI system didn’t introduce any subtle mistakes (which these systems often do).”

Even leadership isn’t immune to the encroachment of machine learning. “Some people think that management roles would be the last jobs to be automated because they require so much insight, decision making, and judgment,” says Kathryn Zickuhr, a senior labor market policy analyst at the Washington Center for Equitable Growth. “But a lot of management functions are already automated. A lot of companies are already using automated or algorithmically-driven management softwares and services.”

The golden age of the growth mindset

There’s no question that AI will eliminate the need for at least some jobs, including highly skilled ones. But that isn’t necessarily a bad thing. As Linzen and others suggest, the automation of rote processes still requires the supervision of humans with expertise – and might even free up organizations to pursue bigger, more ambitious endeavors, as long as they’re prepared to meet the challenge.

The AI renaissance may also prove to be a golden age for organizations that adopt a “growth mindset” that allows them to use new tech to their competitive advantage. The term was coined by the psychologist Carol Dweck to describe high-performing teams and organizations that aren’t afraid to take risks, who embrace big goals and the opportunity to expand their skills and prove themselves, and, crucially, who aren’t attached to old processes and work styles but eager to try new ways of doing things, using new tools.

That includes making peace with the bots.

“I think that AI tools like ChatGPT are best viewed as writing assistants,” says Linzen. “They might make it easier for you to produce a readable paragraph that expresses an idea, but it’s still your responsibility as a human to edit that paragraph to make sure it expresses the idea you had in mind.” Thinking of new technology as just one more set of tools to round out your teams’ toolbox will better equip organizations and individuals to make the most of the exciting future of work.