The path to professional achievement seems like it should be straightforward: work hard, acquire new skills, perform above expectation, and reap the rewards of opportunity and career advancement. In practice, however, job success isn’t solely the result of merit-based recognition, nor does good work always pay off in the ways people might expect. Experts in management and human resources generally acknowledge an open secret that others may not even be aware of: It is possible to be too good at your job. In fact, being too good at your job can set back your professional trajectory for years to come.

The very notion of a penalty for overperformance runs counter to everything we’re taught, beginning in childhood, about the payoff for hard work and a job well done. But it’s important to remember that organizations are composed of individuals whose personal interests will sometimes be at odds. Members of a team may be vying against each other for recognition and advancement; managers, meanwhile, are often tasked with making decisions that serve the company’s interests, but which come at the expense of individual workers’ careers. For these reasons, being “too good” at one’s job tends to backfire in a few specific ways.

Fewer growth opportunities

Managers are sometimes reluctant to promote or assign new responsibilities to a high-performing worker because that person is an asset. Advancing the individual within the company might risk compromising efficiency or losing an ultra-effective teammate.

“A telltale sign of a person being set back by over-competence is when a manager says things to an employee like, ‘I can’t afford to let you go,’ or ‘Don’t apply for that new role, I can make it worth your time for you to stay here,’ says Kia Roberts, a former Director of Investigations for the NFL and the founder and principal of Triangle Investigations, a firm that performs third-party HR investigations for companies. “These statements are really not flattery, but an expression of selfishness on the part of management, who is more concerned about work productivity and continuity than an employee’s career trajectory.”

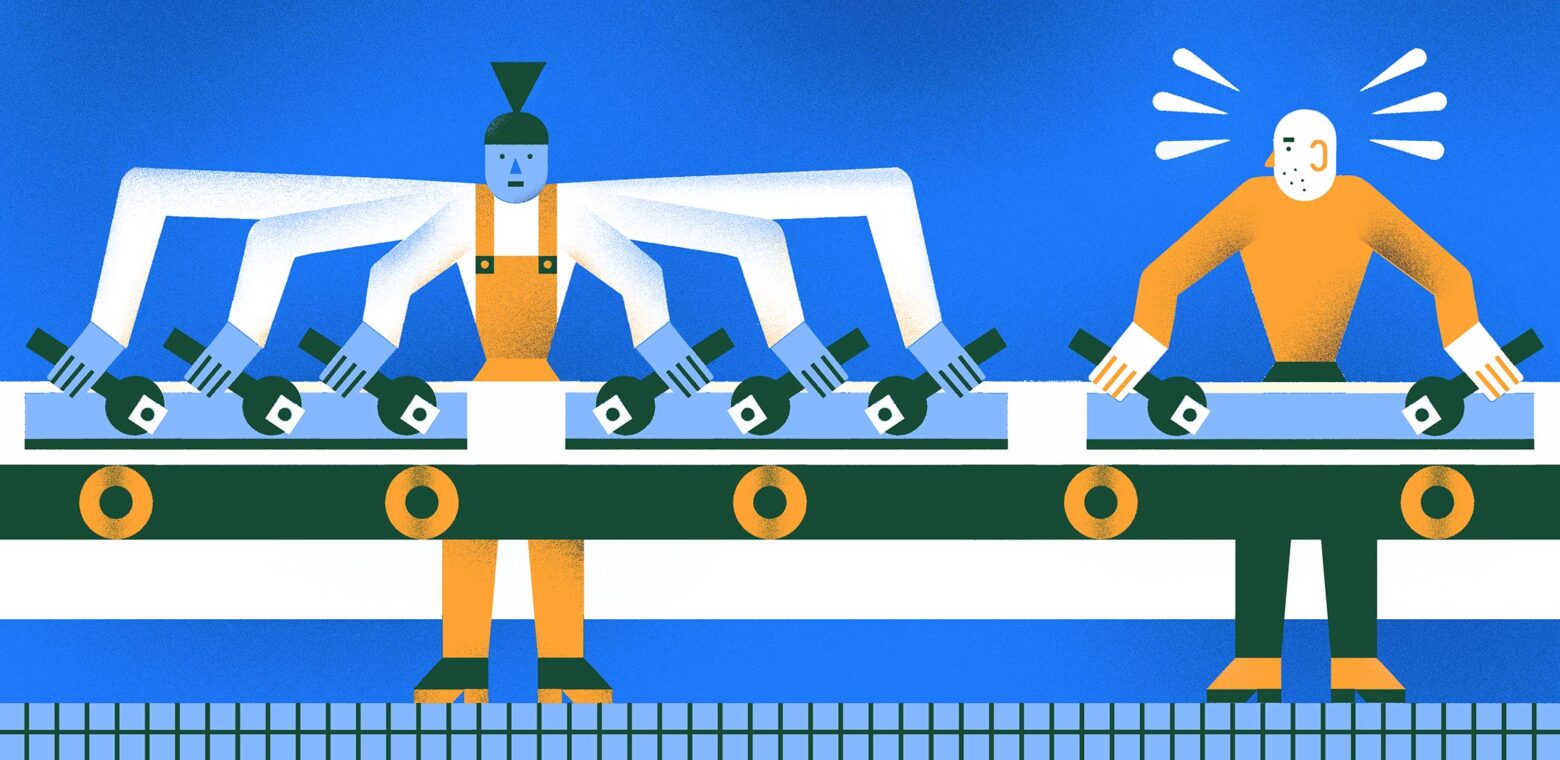

Damage to workplace relationships

If unwittingly, overperforming employees can also alienate colleagues or managers. These workers may even become targets of workplace bullying or see their achievements undermined by others in the organization. “It’s not always the case, but sometimes your coworkers will try to find subtle ways to sabotage your work or your reputation in an effort to make themselves look better and you look worse,” warns Troy Portillo, Director of Operations of Studypool.

Portillo’s observation is echoed by decades of social science research, beginning with a famous 1948 sociology study of factory line workers whose bonus rates could be compromised by the exceptional productivity of a select few. The study showed that a minority of high-performing workers (who had flouted their unit’s collectively agreed-upon productivity quotas) were mockingly nicknamed “rate-busters” by their peers and intimidated to lower their output. Although this is in some ways a unique example – given the circumstances, one could argue that the so-called rate-busters were effectively scabbing – it illustrates how overperformance can pose real (or perceived) threats to fellow workers, particularly in job environments where employee power is tenuous to begin with. Overperforming workers, in turn, incur social ramifications from peers.

Burnout

And finally, there’s the most straightforward overperformance setback of all: Burnout. Workers who are particularly efficient and effective may face pressure from management to take on more and more responsibility within the role, increasing their workloads without necessarily supporting their continued professional growth. Research shows that working without a clear sense of impact might be an even greater risk factor for burnout than heavy workloads themselves.

No matter how they take shape, professional setbacks related to over-competence “can be frustrating for any employee who is on the receiving end of them,” says Roberts, the workplace investigations professional. But it’s important to note that not all workers are affected equally by this phenomenon.

“These feelings can be especially slippery when the setback touches employees who are members of historically marginalized groups,” Roberts continues. “It is very difficult for these employees to discern whether the treatment that they are receiving is due to over-competence, or based upon legally protected characteristics like race, ethnicity, gender, and sexuality.” There is some data to suggest that high-achieving workers who belong to minority groups may be particularly vulnerable to ostracization in the workplace; the over-competence penalty can be seen, in some respects, as an inclusivity issue.

The penalty on high performers ultimately comes down to organizational dysfunction. The onus, then, falls on companies to prevent talented workers from losing opportunities because of their ability. Workers can, however, adopt a few key strategies to protect themselves from the over-competency trap, such as making sure to be team players who help their colleagues succeed; focusing on improving their communication, leadership, and problem-solving skills; and seeking feedback from supervisors and peers. Although these measures may help, workers in this predicament might best be served by cutting their losses and finding new employment.