5-second summary

- The team that brings you this publication experimented with a four-day workweek for nine weeks in summer 2021.

- The sky did not fall! In fact, we maintained or improved on our key performance metrics and felt an improved sense of wellbeing.

- While the experience was positive overall, there were some logistical and emotional struggles.

There’s nothing magical or preordained about the five-day, 40-hour workweek. It’s just where we landed after labor movements made their last push for more humane working conditions. And that was nearly a century ago. Surely, with all the technological advances since then, our workweeks are due for an upgrade.

This may explain why the four-day workweek is having a “moment” right now. Our team has been intently following the glowing press coverage of Iceland’s national experiment, Kickstarter’s trial, and others. Story after story tells of improved employee wellbeing with no dip in performance.

But we wondered if these stories were too good to be true. It’s rare to see anything beyond vague, high-level evidence to back up these claims. So I pitched our manager on running a team experiment so we could find out for ourselves. (It wasn’t a tough sell.)

You would think that, given the chance to work fewer hours for the same pay, people would jump at it. So imagine my surprise when I presented my team with the idea and they did not erupt in universal celebration in response.

Some were skeptical. Can we really get everything done in four days? Will we be a bottleneck for other teams? Is this going to get us fired? I felt confident the answers were yes, no, and probably not.* But their concerns were enough to give me pause.

Ultimately, the promise of a summer filled with glorious three-day weekends won out. We gamed out some “what if?” scenarios, made a plan, took a deep breath, and gave it a try. And we collected a bunch of data along the way.

*Just kidding. We cleared the idea first, so we knew we weren’t risking our jobs.What we hoped to learn

Every good experiment starts with a hypothesis. But our team prides itself on being a little “extra,” so we came up with two:

- We believe our team can be just as effective working four days each week as we can working a traditional five-day week.

- We believe switching to a four-day workweek will have a positive impact on our work-life balance and well-being.

Parkinson’s law says that work “expands” to fill the time you allot for it. So we suspected that the inverse must also be true: we could work more efficiently simply by allowing ourselves less time. This could translate to more intense workdays with fewer breaks, shorter meetings with less space for chit-chat, the need for working lunches, etc. But we also suspected that having consistent three-day weekends would give us the energy to power through.

Plus, having more time to attend to the business of our personal lives should, in theory, make us calmer and more focused during work hours. And the extra day off might open up more time for family, friends, excursions, hobbies… all the things that boost a person’s mojo.

As a bonus, we also hoped to answer a couple of related questions:

- Are there more streamlined ways of working that we can carry back into our five-day weeks after the experiment?

- Are there hidden trade-offs involved in compressing the workweek into just four days and, if so, what are they?

How we set up the experiment

The participants were six individual contributors and one manager. We were located across the U.S., from Hawaii all the way to New York City.

Our team works with nearly every part of the business, from product development to product marketing to investor relations. So we created a page (in Confluence, naturally) to keep our stakeholders and frequent collaborators in the loop. We didn’t want anyone to be caught flat-footed on our day off.

Here’s the structure we used:

- Run the experiment for nine weeks, from mid-June to mid-August.

- Work Monday-Thursday, as close to eight-hour days as possible.

- Mark our calendars as “out of the office” and set our Slack status to “away” on Fridays. Some of us included our cell numbers in our Slack status in case anyone urgently needed us.

- Include checkpoints at the four- and six-week marks. If things went so poorly that it would be professionally or personally damaging to continue, we agreed to end the experiment early.

What we measured

Aside from having a great story to publish, we wanted to contribute to the body of knowledge around four-day workweeks in a concrete way. So we tracked both quantitative and qualitative measures.

On the quantitative side, we tracked:

- Work Life readership, as measured by total page views

- Newsletter subscriber growth

- The number of days we worked longer than eight hours

On the qualitative side, we use a scale of one to five to capture:

- Our energy levels on Monday morning

- Our start-of-week confidence levels in our ability to accomplish everything we needed to during the next four days

- Our Thursday-afternoon satisfaction levels with what we actually got done that week

- Our end-of-week energy levels before signing off for the weekend

Atlassian keeps historical data on readership and subscriber growth, which was like having a quantitative control group baked right in. For the qualitative data, we started the tracking a few weeks before the experiment started so we had a baseline comparison.

Alongside the qualitative ratings, we recorded why we felt that way. All the quotes you’re about to see come from those comments.

Here’s what the data revealed

First, the simple fact of running this experiment reveals that our team is a lucky group of humans. It’s a privilege to work at such a forward-thinking company and to have the kind of flexibility our job roles afford.

Now, about that data…

What happened to our energy and focus at work?

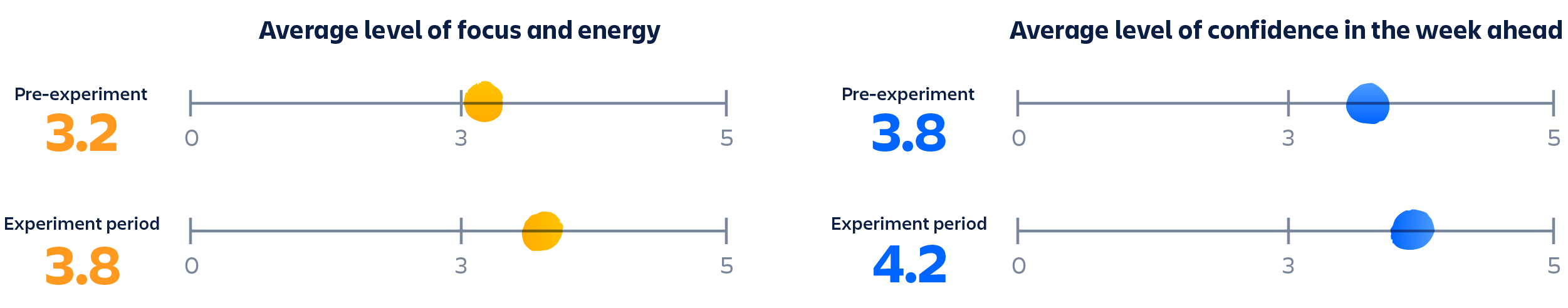

Overall, we were more motivated on Monday mornings during the experiment compared to before – both in terms of our energy levels and our confidence in our ability to get everything done by the end of the week. During the experiment our ratings for energy averaged 3.8 out of a possible five points, and 4.2 for confidence, whereas before the experiment, ratings had averaged 3.2 and 3.8, respectively. As one team member said, “It’s easier to start work on Monday knowing that your next weekend is only four days away.”

Our ratings varied somewhat week-to-week. Although there were no zero or one ratings for energy and confidence, there were a handful of twos.

According to the accompanying comments, the driving forces behind those lower ratings were evenly split between personal and work-related factors. “I’m just tired because I didn’t sleep well last night,” wrote one team member. “A couple of tasks are dependent on contributions from other people, and some of those people are running behind,” said another.

As the experiment wound down, our Monday morning mood did, too. Was this a natural fluctuation? Or, were we sliding into our version of the “trough of disillusionment”? Since the downturn happened in the final weeks, I can’t say. (Clearly, further research is warranted. 😁)

What happened to our performance as a team?

Simply put, we performed well. Our absence on Fridays didn’t cause friction with other teams (proactive communication for the win!) and we didn’t miss any deadlines. “This week I had to work with a ton of different people. Thankfully, all of them were very responsive,” wrote one team member early in the experiment. “I was able to get everything on my list done!”

In fact, we pulled off a few high-profile projects like the debut of the Teamistry podcast’s third season and the launch of Atlassian’s second annual Return on Action Report. Buoyed by these wins, our satisfaction with what we accomplished each week trended upward throughout the experiment. By the end, we were recording a lot of fives in that area.

With Friday off and the upcoming July 4th holiday, I’m a bit concerned about getting to everything. But in a strange way, that’s motivating.

And the numbers back up this feeling! Readership was actually 5.2 percent higher during the experiment period, compared to the same period last year. And our newsletter subscriber base grew by 8 percent. That said, subscriber growth was slightly lower during the experiment compared to the months immediately prior. But since most of our audience is in the northern hemisphere, a summer slump in June, July, and August is typical for us.

How did we pull this off? “Setting aside interruption-free time to focus was key for me this week,” one person noted. We also aimed for fewer, shorter meetings, and we scrutinized the value of each task or request so we stayed focused on high-value work.

For me, it was mostly a matter of trimming the fat to create denser, more nutrient-rich workdays. When working five days a week, for example, I would take a mid-morning break to scan the news and have a second cuppa. But during the experiment, I sipped my coffee while reading something work-related.

This was a good week. I’m definitely living Parkinson’s Law! With less time to work, I’m forced to work with more focus. I’m fascinated by this.

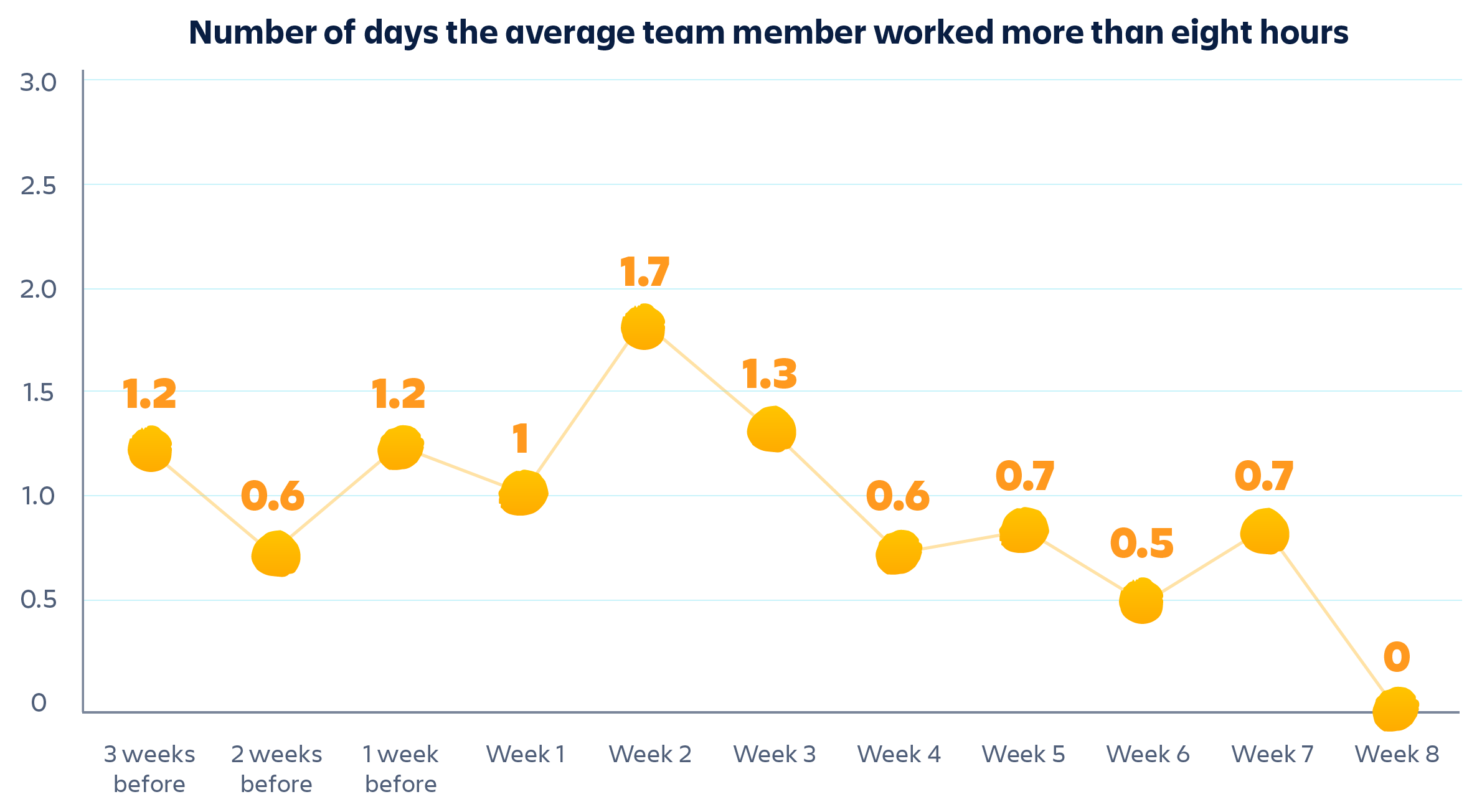

This new way of working did take some getting used to, though. In the first few weeks of the experiment, we worked over eight hours a day more often than we did pre-experiment. Our notes reveal that we didn’t yet believe we could really be just as effective in our jobs while working only 32 hours each week, so we (over)compensated by working later.

We dropped comments like “I started Monday feeling confident, but felt overwhelmed by the end of the day,” and “I’m feeling the Thursday sign-off scramble!” By the end, however, we’d gotten the hang of it and were working eight-hour days almost exclusively.

What happened to our sense of wellbeing?

When we held a retrospective after the experiment, everyone on the team said the overall experience was positive – and for some, very positive. It wasn’t all sunshine all the time, though.

For me, every interruption felt like a catastrophe. As if taking 30 seconds to pour my son a glass of milk guaranteed I’d need to work late that day. (Turns out, it didn’t.) But I’m high-strung to begin with. My teammates who are more laid-back and/or weren’t surrounded by school-aged kids on summer break didn’t experience this.

That said, everyone reported feeling nervous sometimes about whether they were doing enough, working enough, or being effective enough. (Turns out, they were.) But whatever angst we felt was overshadowed by the promise of a three-day weekend just around the corner.

As we near the end of our experiment, I really can’t say I’ve experienced many negatives. Almost entirely positive for me. Work is getting done, I’m feeling motivated, and am really enjoying the extra personal time.

Having Fridays off was awesome. Can’t say it enough! Most people used that time intentionally: a dedicated day for hobbies and projects, excursions with the kids, or knocking out chores so Saturday and Sunday were purely for recharging. Others reveled in the freedom to let the day unfold organically and just go with the flow.

Either way, the positive impact on our well-being can’t be overstated. Considering the current climate of pandemic-induced anxiety and generally exacerbated social toxicity, the emotional boost was right on time.

A person could get used to feeling that good.

Beyond the data: 4 takeaways from the experiment

We learned a metric tonne about ourselves from this experience – not to mention a few lessons that anyone can apply in their quest for better work-life balance. Highlights include:

1. Parkinson’s Law is real!

And the inverse is real, too. You can deliver just as much value in less time if you’re disciplined about it.

💡Idea: Try giving yourself a personal deadline to deliver a project one day earlier than you ordinarily would, and get some first-hand experience with Parkinson’s Law.

2. Not all tasks are created equal.

Prioritizing tasks and scrutinizing which ones really add value is key.

💡Idea: Choose a low-value recurring task, e.g., a status update on a non-critical metric, to stop doing. Yes, it’s uncomfortable. And down the road, you might have to put that task back on your plate. But the upside is worth the risk.

3. A rigid schedule can still be stressful – even if it affords you more free time.

You can’t always control when “life” happens to you. Flexibility matters.

💡Idea: If you’re in a role where working from home or outside the traditional nine-to-five workday is possible, make the case to your manager as to why and how you’d like to build in more flexibility.

4. Extra time off from work is wonderfully restorative.

We often forget that in our productivity-obsessed culture. Indeed, American workers only use about half their vacation time, and two-thirds report working even when they do take time off.

💡Idea: Use your dang vacation days! And log out from all your work apps when you do.

💡💡Bonus idea: If you’re in a leadership position, declare a department-wide day off. With everyone off at the same time, nobody will feel like they’re leaving anyone hanging or need to check in. This technique is trending across Atlassian and, so far, it’s proving to be effective.

So, what’s next?

Atlassian isn’t considering a company-wide shift to four-day workweeks, but our team is already applying the lessons we learned. We are building in extra time to recharge with a monthly day off for the whole team, and by taking time to celebrate when we ship big projects. We’re looking at designated meeting-free days to increase our heads-down focus time. And we’re even considering instituting occasional “days of wonder” dedicated to exploring new ideas.

We’re also taking time to share what we learned and encourage other teams to run experiments of their own.

What it means to you

Obviously, your ability to change to a four-day workweek is dependent on many things and the decision may not be yours to make. However, there may be other ways to achieve a little more work-life balance. Depending on the work you do, you might stick with five-day workweek, but get the green light to work fewer hours each day. Research shows even a slight reduction in work hours can have tangible benefits to your health and wellbeing.

There’s no rulebook on this yet, so you might as well get creative with the format!

Now is the perfect time to explore the idea of a more flexible work life. Now, while we’re already neck-deep in reinventing the way we work. Now, at a time when workers are so totally over overwork that a majority are willing to turn down a promotion in the name of preserving their mental health, as Atlassian shared in our 2021 Return on Action Report.

As we re-evaluate the role work plays in our lives, employers have a unique opportunity to help their people – and themselves – find a sustainable work-life balance. Because if we’re working so much it takes over our lives, then neither work nor life are very much fun.