I’m a product designer. I’m also a black woman.

Exploring the intersection between my professional and personal identities is really important to me. Particularly because, at their core, I believe design and diversity are both practices in focused, actionable empathy.

To test this theory, I applied my design process to my hair. That is, I used a comprehensive product design process to tackle one of my biggest challenges in self-care: my kinky-curly hair. Here I would like to share my findings with you. My hope is that reviewing this particular application of the product design process will not only help you learn more about it, but also shed light on how we might increase empathy for the diversity presented by the world around us. You might even learn a thing or two about your hair!

The high-level gist

Let’s start by reviewing each step of the product design process. As we move through the process, we work towards answering questions designed to build iteratively a larger field of understanding.

- Understand and define the problem: What, exactly, is the problem we want to solve? Why do we want to solve it?

- Outline desired outcomes: What does success look like? How do we measure it?

- Gather solution-centered data: How have other people in similar situations solved similar problems?

- Create hypothesis-centered solutions: What solutions do we believe will address the problem? What affects do we expect them to have? Why?

- Implement, iterate, and simplify: Are we proposed solutions having the desired affects?

- Identify areas for improvements: In what areas can we get better?

Understand and define the problem

What, exactly, is the problem we want to solve? Why do we want to solve it?

In product design, there are many methods for understanding the problem we need to solve. However, one thing remains constant: All problems (should) be centered on spending time with target customers. In this case, I am my own customer, in that I am working with my own hair.

You might be asking yourself: “Is hair really that hard?” Well, it depends. Things like genetics, environment, and fundamental hair structure are large contributing factors.

In the case of my hair, the answer is a strong yes.

This particular hair journey begins in 2011. That’s when I decided to do a “big chop”: I shaved off my chemically-straightened hair and started completely over. The true health — or lack thereof — of my hair became apparent when I shaved my head — I quickly realized I was dealing with chronically dry, brittle, broken hair that couldn’t handle any level of manipulation without showing signs of stress. The stuff that worked when my hair was straight refused to work when my hair wasn’t.

What I love about this problem is that there is far more than meets the eye. This isn’t as simple as going to the store and buying a new conditioner. So let’s unpack this.

Structural context

As I would with any design project, I looked at this with extreme objectivity. I began with fundamental questions:

-

- What is hair?

- What can make hair so brittle?

- How common is this problem?

- What conditions may have contributed to this current state?

As many of us know, hair comprises fine, multi-layered, threadlike strands. The structure of the hair shaft is reinforced by the protein keratin.

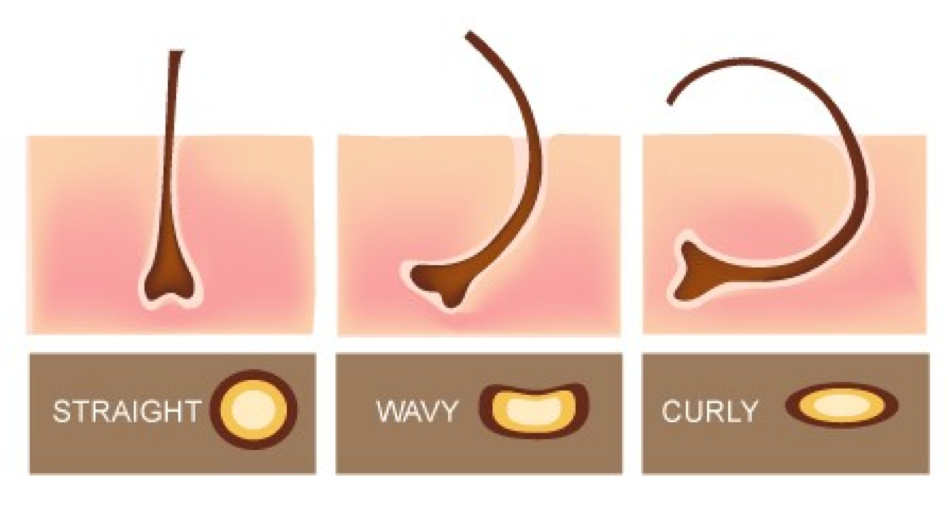

Now, the shape of the cortex determines the angle at which the hair comes out of the scalp. The more non-round the cortex, the more likely the hair is to emerge at an angle, which creates a wavy or curly pattern.

Curl along the full strand of hair, however, comes from the abundance of disulfide bonds along the hair shaft. The more disulfide bonds present, the curlier the hair. The curlier the hair, the higher the chance that individual hairs will rub against each other. This friction can weaken the overall structure of the hair shaft. This means that kinky curly hair is more likely to have a problem with strength and moisture.

At this point we understand how and why my hair is curly. We also understand that its curly nature makes it more prone to dryness and breakage than straight hair.

The advantage of having hair this curly is its flexibility — the curliness provides structure and hold for any number of styles — braids, puffs, locs, extensions, straightening, etc. Despite some of its disadvantages there is a beauty in the wide variety of styles curly hair is capable of.

Now that we understand the scientific structure of hair, it’s important that we look at an additional factor contextualizing this problem: culture.

Cultural context

Next, I looked at the issue through another lens: culture. Again, as I would in my design process, I considered questions like:

- What forces are influencing the problem?

- What forces might be keeping it in place?

This is a rather complex question when it comes to black hair.

In the context of western society, and especially in American culture, we’re shown through magazines, television, the Internet, etc. that a specific standard of beauty exists. That standard usually aligns with women with straight or wavy hair, and typically lighter skin. Most of the time, these women are white or white-appearing.

Living in a society with a specific standard of beauty means pressure to subscribe to said standard, and this was particularly true for me when I was growing up. As a child, I was told that my hair in its natural, curly state was undesirable, ugly, and unpresentable. Since I was very young, my parents took me to get my hair chemically straightened once a month.

I hated this stuff as a kid, and so did my scalp.

Though this number has been decreasing, many black women relax their hair or straighten it with heat, processes that either permanently or temporarily denature those aforementioned disulfide bonds to give the hair a straighter look.

The news is rife with examples of how beauty standards influence attitudes and policy. Until late 2015, the American military banned dreadlocks, twists, braids and similar styles, which are popular styles with busy black women. In some states, it’s legal for companies to terminate employees if they don’t “remove” their dreadlocks — which, in most cases, means shaving one’s head. Similar policies are seen the world over.

Society has sent a message loud and clear: to be considered acceptable or presentable, one must shave off or straighten their “unacceptable” hair. While straightening one’s hair through whatever means does not imply that someone is doing so exclusively due to societal pressures, this does not deny that these expectations exist.

Much empirical evidence shows that biases towards black people, including traditionally black hair styles, exist, and affect how black people perceive themselves relative to the world around them. These studies are depressing, but fascinating, important, and even comical — especially when you consider it all boils down to the shape of one’s cuticle and the amount of disulfide bonds along the hair shaft.

So, what does this mean for my hair? Well, in 2011, it meant I was starting almost entirely from scratch. Since I’d been straightening my hair most of my life, I didn’t know how to take care of it when it was curly, or in its natural state. I couldn’t ask my mom or many of my friends, because their hair was either still straight, or they were in the exact same “I just shaved my head” pickle as me. Due to the societal standards mentioned above, there’s a limited understanding of how to take care of black hair in the hair industry, and therefore a limited amount of products. Any available products were very expensive. Not so great for someone embarking on a major trial-and-error endeavor.

We’ve spent a lot of time going over the structural and cultural context of African-American hair. We see a history of bias and discrimination, which has lead to a limited availability of products and a limited distribution of knowledge. As like with actual product design, this step in the process is where I spend the bulk of my time. After all, if I lack a thorough understanding of the problem throughout the remainder of the design process, my solutions may be entirely inappropriate.

The lesson here is that any and all context matters. Look the most closely at the things that are present but seemingly unrelated. Those details usually represent the biggest learning opportunities and insights.

Outline desired outcomes

What does success look like? How do we measure it?

Now that we understand our context, we can start to consider what a “perfect world” might look like. What does success mean for me? How to measure whether or not I’ve met my goal? Here, it’s especially important to make sure there’s a clear definition.

Here’s my desired outcome:

My hair is healthy and my hair care routine is sustainable.

Now, I can guarantee that every person reading this article is going to have a different interpretation of the above statement. When creating these desired outcomes, it’s important to explicitly define any words or phrases that may carry ambiguity or be interpreted differently. By doing so, we not only reduce opportunities for misalignment, but we naturally create a way to define and measure success.

I can say that I want my hair to be healthy, but what exactly does that mean? Does it mean my hair goes to the gym thrice weekly? No? Then we need to break this word down more to have a clear meaning in this context. I know my hair is “healthy” when it is:

- Moisturized – My hair is soft, flexible, and moves freely.

- Strong – My hair is s unbroken and can be manipulated without pain or damage.

We now have a clear definition of “healthy” and how we might best measure it. Next, let’s apply the same method to the term “sustainable”:

- Cost-effective. I can do the same hair care routine at a reasonable interval without running out of money.

- Time-optimized. My routine is not so intense I have to spend hours a day working on my hair, nor is it so short that it has a negative impact on overall hair health.

Now, let’s combine the goal and its breakdown and formulate a “How Might We” question. HMW questions are a great way of framing the problem that implies flexibility and compels action, such that there’s always the possibility of a wide range of solutions, but narrow enough to establish appropriate bumper lanes.

In this case, a HMW:

“How Might We (or how might I) build a sustainable routine optimized to create healthy hair?”

Again, it’s very important to check in with our customer (me) and make sure we’re on the right track. This can be as simple as asking them directly for feedback. “Am I missing anything?”

At this point, we have a clear idea of what success looks like as well as how to measure it. We have taken this information and framed it in the the form of an actionable “How Might We” question.

Gather solution-centered data

How have other people in similar situations solved similar problems?

Now it’s time to explore solutions. One way of doing this is to look and see how this problem has been solved before. We can look at similar situations, ask ourselves why those solutions were chosen, review what has and has not been tried, and consider what might work best in our context.

It’s also important to identify which situations don’t have an appropriate amount of context, but should still be taken into account. Watching a video of someone straightening their hair might be helpful, but isn’t exactly what I’m looking for here; I don’t need to straighten my hair, just keep it healthy. Checking back in with our ideal world — centered around health and sustainability as we have defined them — is a simple way to measure the appropriateness of a solution. With every idea we have, we must ask ourselves: do we believe it will help us move towards our ideal world, and if so, how?

Thankfully, we have the Internet at our disposal, which makes it exceptionally easy to poke around and find solutions for similar problems. And there are plenty of situations out there in which people care for their hair. There are also situations that have little to do with hair, but can still be taken into consideration. For instance, cuticles are the same stuff that make up our nails and skin. If we look at nail and skincare, we might consider solutions there.

Now, it’s important that we don’t just blindly copy a solution. First, we must ask ourselves why that solution has been applied and what purpose it serves. For example, apple cider vinegar, diluted with water, is often used as a hair rinse because hair is relatively acidic. Water is more basic than our hair, so by washing our hair in water, we pull it away from its natural pH. Apple cider vinegar rinses can help return the hair to its acidic state. This can help the cuticles of the hair function properly. It also keeps the scalp clean and free of debris. Pretty cool, right?

Another technique is leveraging the temperature of water to influence cuticles. Cuticles can be described as little doors along the hair shaft. When open, they can let moisture in and out. When closed, they lock in whatever is inside. Warm water opens the cuticles, maximizing absorption of moisture. Cool water closes the cuticles, locking in this moisture. Therefore, if we wet the hair with warm water before applying conditioner, then use cold water to rinse it, we can keep hair as moisturized as possible for longer.

Create hypothesis-centered solutions

What solutions do we believe will address the problem? What affects do we expect them to have? Why?

Once we find solutions we would like to try, it’s important to be explicit about their purpose, and what parts of the problem they are solving. This can accomplished by following the following formula:

We hypothesize that (solution) will address (problem) by (having desired affect).

Let’s apply this concretely. Given the solutions explored above, we can hypothesize that:

- A regular protein treatment (solution) will address chronic dryness (problem) by reinforcing the hair structure over time (desired affect).

- An apple cider rinse will help welcome moisture by balancing pH levels and clarifying the scalp surface.

- Rinsing the hair with cool water will help lock in moisture by closing the cuticle along the hair shaft.

This exercise may feel excessive, but this is critical to building a shared understanding of what solutions we are trying, and why. Don’t forget to continually check in with your customers and ensure you are headed towards the most appropriate North Star.

Implement, iterate, and simplify

Are we proposed solutions having the desired affects?

Now for the fun part: trying out proposed solutions. At this stage, we have our hypotheses and it’s time to test them against our goals and make adjustments. This stage is cyclical: come up with a solution, test it, and adjust.

Depending on your problem, you can try low-fidelity drawings, role-playing, customer interviews, and more. Be creative in finding ways to validate your solution. Remember that this isn’t about you, it’s about your customers (unless, of course, you are explicitly your own customer). Ultimately, if your solution does not work for your target demographic, all of your hard work will be for naught.

In my case, this was a matter of buying a whole bunch of products and trying them out. In essence, I became a product junkie. Some products were great for protein, but left my hair feeling too heavy. Others were great for moisturizing, but were way too expensive. Some methods didn’t work at all, and others simply took too long.

Identify what isn’t working and put it to the side, but don’t throw away. What doesn’t work today might be needed tomorrow.

When I finally discovered what worked for me, I optimized my hair care routine for simplicity. I figured out which products worked, how I should use them, and how quickly I could do the routine without sacrificing effectiveness.

I arrived at this routine:

- Apply warm oil directly to the scalp to moisturize it.

- Shampoo my hair with warm water to open the cuticles.

- Condition hair with a protein treatment mixed with conditioner. Cover hair with plastic cap and use heat from a hair dryer to keep the cuticles open.

- Rinse hair thoroughly with cool water to close the cuticles.

- Evenly apply a lightweight leave-in conditioner.

- Evenly apply a lightweight oil (such as almond or coconut) to smooth the cuticles and seal in moisture.

Identify areas for improvement

In which areas might we get better?

At this point, I have a defined routine. My product, so to speak, has been released into the wild.

But my work isn’t done, and neither is yours. I always take the time to review my routine, weigh its affects against my goals, and make adjustments to keep me on track. New products are released all the time, and my current products can change ingredients. More and more methods and routines are being shared widely. I spent 7 years working on this, and I’m still learning and iterating to this day. It’s a process of constant learning, and it’s exceptionally fun.

Conclusion

Remember to cultivate a sense of curiosity and tenacity for understanding in every aspect of life. Throughout the process, keep an open mind. There will be inevitable surprises, twists and turns – that’s the good stuff! And consistently check assumptions with research-derived insights.

In my job as a product designer, I like to spend most of my time at the beginning of the process, establishing a solid, understanding-based foundation upon which I can explore and build solutions. Ultimately, if I don’t fully understand the problem, the solution will not be appropriate for it.

And, remember: We will rarely be our own customers! They will be out in the wild somewhere, operating in their specific contexts. We can’t assume what works for us will work for them, especially if we’re not aligned by target demographics. For example, if we’re creating an augmented reality product for teenagers to decorate their rooms, we can’t assume things we like (if we’re older folks) will match what teenagers like. In this particular case, I was my own customer. That made things more straightforward!

One of the most important things about product design — and diversity —is learning to step outside of ourselves and consider the needs of a person or group of people we’re unfamiliar with. With that, I encourage you to go forth and build those empathy muscles.