Win at quarterly planning by avoiding these OKR mistakes

OKRs are a great tool for quarterly planning. But let’s face it: they can trip you up at first. Set yourself up for success with these 8 tips.

The moment I heard it, my acronym allergy kicked in: OKRs. I’d done S.M.A.R.T. goals at another company, and the way we did them didn’t pan out. Ditto quarterly As & Os (accomplishments and objectives). Obviously, this OKRs thing was going to be more of the same. One big mistake.

And they did indeed kind of suck. We’d start working out OKRs for the next quarter with a full month left in the current quarter, so it felt like we were always in planning mode. Then all quarter long, I’d go down my checklist of KRs doing the same things I’d probably be doing anyway, wondering how that month of formalizing them wasn’t pointless overhead.

OKRs (“objectives and key results”) n. — Yet another corporate goal-setting framework.

The one thing OKRs had going for them was that people up the chain were setting high-level objectives, then leaving it to the people closest to the actual work (i.e., people like me) to decide exactly how we were going to contribute. That part totally makes sense, and I appreciate that level of autonomy.

Still, OKRs felt like a confusing and unnecessarily process-heavy way of shooting for the stars.

Then I realized I’d been doing them wrong in a bunch of ways. In fact, most of us were getting something about OKRs wrong. No wonder it was confusing. Long story short, we straightened ourselves out and now OKRs are actually fruitful — I’ll show you some real life examples below.

If you hate OKRs, you owe it to yourself to at least make sure you’re doing them right (seeing as you probably have to do them anyway, rage notwithstanding). Below is a list of mistakes that were running rampant around Atlassian, plus a couple bonus anti-patterns you should be aware of.

Full disclosure: we haven’t eliminated all of them. Yet.

What are OKRs, anyway?

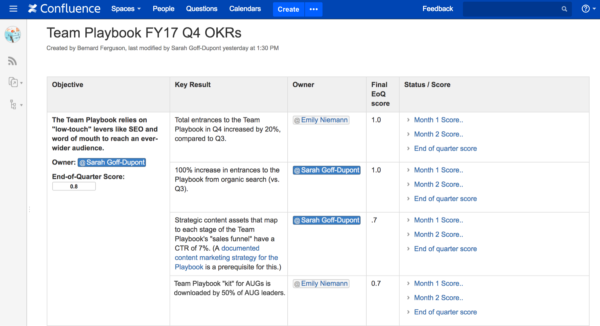

“Objectives and key results” (OKRs) is a framework for setting goals, typically on a quarterly basis. Your team sets 3–5 high-level goals (objectives) to pursue, along with 2–3 success measures you’ll use to determine whether you’ve reached it (key results).

At the end of the quarter, you score each KR on a sliding scale from 0 to 1 (0 = no progress at all; 1 = you hit or exceeded your target; .1-.9 = somewhere in between). During the quarter, you check in and predict what the final score will likely be, based on how you’re tracking so far. This keeps OKRs fresh in your mind and serves as an early detection system for OKRs that might need some extra attention.

Mistake #1: confusing themes with objectives

“Ecosystem” isn’t a helpful objective. Neither is “customer experience”. They don’t say much about what you’re trying to achieve or where you want to go. They’re nice themes, sure. But they’re not really goals.

Instead, write your objectives such that you can look back later and see clearly whether you met it or not.

One of our design team’s objectives is “Improve our craft, velocity, and quality of design decisions”. They paired it with KRs like “50% of product releases have a passing UX scorecard”. (I don’t know what a UX scorecard is, but I trust our design team does.)

Mistake #2: capturing all your work as OKRs

Your KRs shouldn’t be an exhaustive list of every single thing you and your team are doing. Stuff that falls into the “business as usual” category like fixing bugs or closing out the quarterly books doesn’t need to be there.

If your objective is to change the way in which you go about business as usual, that might be worth including — “Improve turn-around time on customer-reported bugs” or “Reduce late expense report submissions by 20%”.

OKRs are your highest priority items, and “just enough” is enough. FWIW, I’m a senior-level individual contributor and I typically own 1–3 KRs each quarter.

Mistake #3: confusing key results with tasks

For a long time, I wrote my KRs as nothing more than a to-do list. Check ’em off when they’re done, score ’em all a 1 (more on that in a moment), and call it a day. Satisfying, sure… but again: formalizing my tasks as KRs just felt like busy work. Plus, there were times when, halfway through the quarter, I realized the task wouldn’t get me closer to the objective. “But it’s a KR! I’m honor-bound to follow through on it!” Ugh.

My lightbulb moment was when I got hip to the fact that the “R” stands for “result”. (Duhhh.)

So instead of saying “Publish 3 blog posts related to the Team Playbook”, I started saying “Increase traffic to Playbook-related posts by 15%”. How I get that 15% increase is flexible. I could promote old posts, optimize them for search, publish new stuff, or some combination thereof. Also, getting to a 15% increase feels like a juicy challenge. (‘Cuz honestly, I could churn out 3 posts in my sleep. They’d get crap results if I wrote them that way, but I could do it.)

Tip: Think “outcomes” — not “output”.

Mistake #4: failing to manage dependencies with other teams

Sometimes all the skills and resources needed to reach our goals are right there on our own teams. Sometimes not. Before committing to a KR that depends upon work from another team, make sure they’ll have the bandwidth to deliver what you need.

Mistake #5: scoring key results by gut-feel

You may have seen KRs like “Better customer engagement”. How could you even score that?? It’s super subjective, and therefore meaningless in the context of goal-setting.

When you phrase KRs as a measurable result, however, they’re easy to score. Just do the math. Going back to my “Increase traffic to Playbook-related posts by 15%” KR above, let’s say I manage to increase traffic to my blog posts by only 5%. I divide 5 by 15 and boom: my score for that KR is .3 (roughly).

Objectives, on the other hand, are often articulated such that you can’t score them objectively. But that’s actually ok. Take the average of all the KR scores rolling up into it, and you’ve got your O score.

Mistake #6: scoring key results on the wrong scale

There’s this famous preso from Google about OKRs that talks about how a score of .7 is considered good. That led to some confusion on our team as to whether you score your KR a .7 vs a 1 if you hit your stated target. (The argument being that scoring it a .7 leaves room for you to exceed it and “get credit” for over-achieving.)

Here’s the deal. If you hit your KR’s target, you score it a 1. At least, that’s how Google does it. If you exceed your target, you still score it a 1 — and think about setting a more ambitious target next time. Which leads me to…

Mistake #7: consistently scoring 1s on every OKR

The reason a .7 is considered good is that your stated targets are supposed to be really really hard to hit. If you’re nailing them most of the time, you’re not stretching yourself. Or, your KRs are actually just tasks (see above) that get a binary 0 or 1 score. Maybe it’s both.

My team once set a KR of doubling SEO-based traffic to one of our microsites, which, honestly, felt like a pipe-dream. But lo n’ behold, we did it! And we learned a ton along the way, which wouldn’t have happened if we’d set a target we could’ve sleepwalked to. This was my other lightbulb moment.

Mistake #8: doggedly pursuing a bogus OKR

Don’t keep chipping away at a rock if it’s the wrong rock. Things change, new information comes to light, etc. It’s ok to remove or abandon an OKR if you no longer believe it’s the right thing to do. Score it a 0, and replace it with one that is right.

An important aspect of OKRs is that zeros are not punishable. (If they are, then you’re really doing it wrong.) Instead, zeros should prompt questions. Why did we miss so badly? Why was this the wrong goal? How can we set a better goal next quarter? If you learn something from your zero, you haven’t wasted your time.

It’s OK to hate OKRs… but I don’t (anymore)

After a few quarters of doing OKRs the way they’re supposed to be done (or close to it), I generally feel more focused. It’s easy to figure out what I should be working on at any given point in the quarter. And if someone requests additional work from me, I can weigh it against OKR-related work and give them a yes/no answer quickly.

I also feel more connected to the work people around me are doing (and being a remote employee, that’s doubly important). My teammates and I often own individual KRs that feed into a common objective, which gets us sharing info and ideas more than we used to.

As a bonus, getting comfortable with setting stretch goals keeps me from wallowing in mediocrity. Complacency is a career-killer, and I’ve got too many years before retiring to rest on my laurels just yet.

So yeah: I’ve gone from OKR hater to born-again OKRs booster. Which makes me wonder what else in my life seems kinda sucky… but only because I’m doing it wrong.

. . .

Find complete OKRs instructions on the Atlassian Team Playbook website – our free, no-BS guide to unleashing more of your potential.