This article is the first in a series exploring what a culture of openness really looks like, warts and all, in the words of every-day Atlassians who are living it.

A culture of transparency boosts teams’ performance and sense of well-being, and is overwhelmingly sought after by employees – all according to research we conducted recently. Open dialogue and freely flowing information are simple enough to pull off when the company is 10 people. Or even 100. But what happens as a company grows to thousands of employees? Does openness scale?

The short answer is yes. The full story, though, is more complicated. For Atlassian, transparency has been part of the culture ever since Mike Cannon-Brookes and Scott Farquhar founded the company in 2002 on the back of a $10,000 credit card. But that doesn’t mean the journey through the world of open work has been easy, even if it’s been more about “maintaining and augmenting” than “becoming.”

Meet five long-time Atlassians:

Matt, Lead Principal Architect for Jira

Employee #122

Jay, President

Employee #192

Penny, Senior Engineering Manager

Employee #271

Denise, Senior Operations Engineer

Employee #603

Dom, Work Futurist

Employee #1057

Each of them has watched from a different vantage point as the company has grown from a scrappy, bootstrapped team of 100 to a publicly-traded global enterprise of over 4,000. The six of us sat down for a candid conversation about how Atlassian’s culture of openness has changed (or not).

First impressions of open work

Dom Price started at Atlassian in 2013 as Head of Program Management. He also does a reasonably decent Elvis impersonation.

Dom: “I hated it.”

Denise Unterwurzacher joined Atlassian in 2012 as a technical support engineer. She’s a developer at heart, and will happily talk your ear off about garbage collection in Java.

Denise: “It was pretty amazing. Compared to other places I’ve worked, where management says one thing and behaves in a totally different way, it was really striking.”

Penny Wyatt came to Atlassian in 2009 as a quality assistance engineer. It’s possible that she knows the nooks n’ crannies of Jira better than anyone else on the planet.

Penny: “It was a ray of sunshine. It’s why I’m still here.”

Dom: “In my first 90 days, I was actually looking for other roles elsewhere. I’d worked 13 years in toxic environments and learned very prescriptive ways of surviving, and I didn’t realize how close to me those ways of working were. Now, whenever I published a project plan or whatever, some f#&ker would comment on it and make me feel bad about myself, and I actively hated it. I’d never had in-the-moment feedback like that before.

Even though in my mind I knew it was meant to be good, it didn’t feel particularly nice and I didn’t think I was cut out for it. Eventually, I realized there’s a whole load of context around things like open values that can’t be easily explained. I don’t think they’re human nature. So for me, those first 90 days felt like organ rejection. I got over it, obviously.”

Valuing transparency

Matt Quail joined Atlassian in 2007 as a developer on the Jira team. Inexplicably, he is known around the company as “Spuddy.”

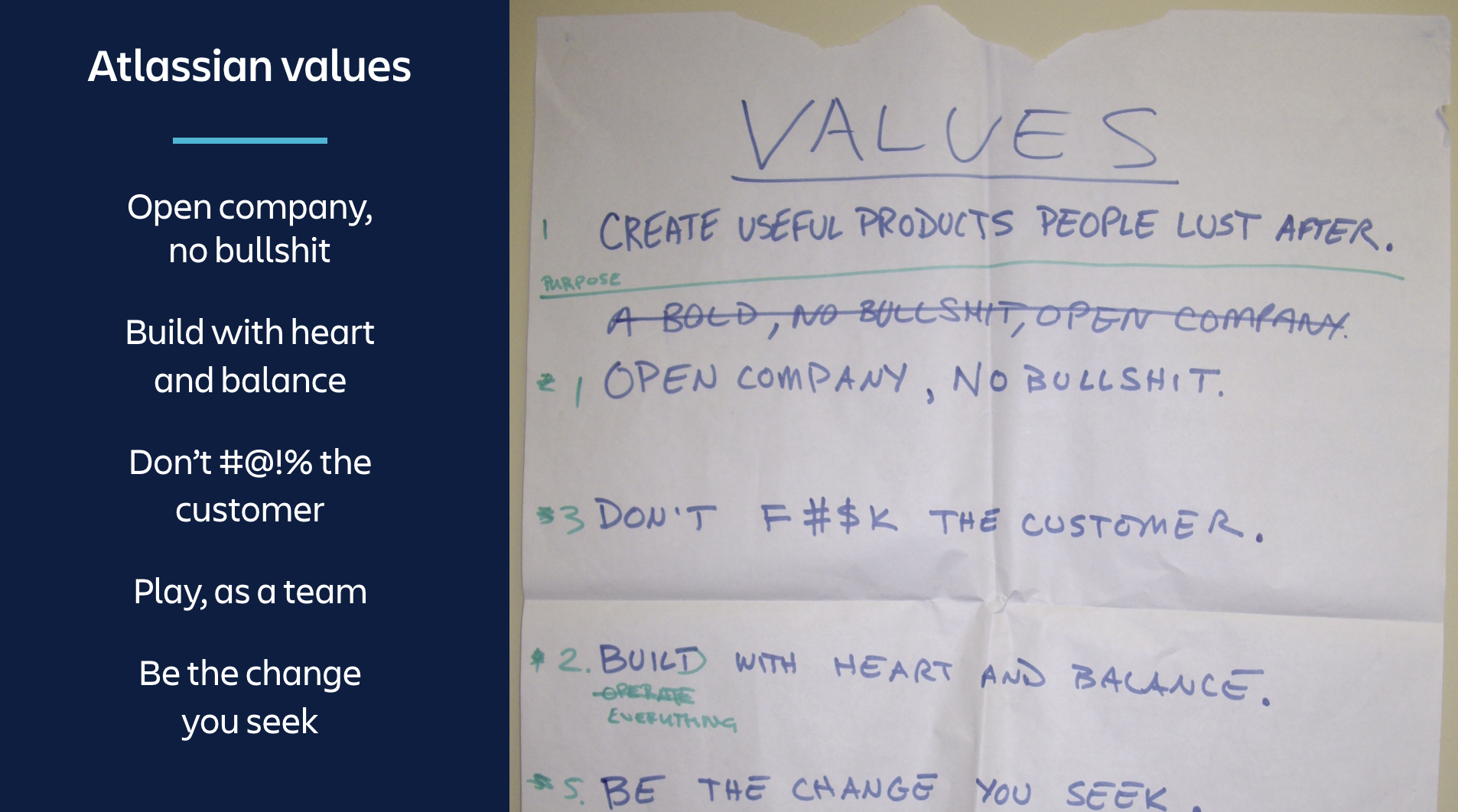

Matt: “I joined just before the Atlassian values were coined. There was a group of five or six people who were tasked with the job of coming up with these values. It felt like their job was not to tell Atlassian what its values should be, but just describe what Atlassian’s values were at that time. It was a description – and aspirational. We wanted to maintain those values going forward.”

Denise: “Around the time I joined, we had a big data loss incident, which was terrible. We were all sitting in the support room on the phone with very, very angry customers. Scott [Farquhar] came down into the support pit with this massive tray of breakfast foods. I had heard the values, I’d heard people kind of give lip service to them, but it was the first time I really saw how deep it actually goes in this company. Everybody here lives the values, from the CEO all the way down.”

Jay Simons came to Atlassian in 2008 as Head of Marketing. He began his illustrious career as a lounge-singer-slash-piano-man in Burma.

Jay: “Part of the reason we had this open culture early on is that we were split between San Francisco and Sydney offices. We needed to be less siloed than other companies. And part of it is because of how we were using our own tools, which are designed to open up work.”

Penny: “Atlassian is not very good at secrets. I think it was Didier [former Head of Jira Service Desk] who said a few years ago that at Atlassian, ‘secret’ means you only tell one person at a time. And that still holds true.”

Challenges to maintaining openness at scale

Dom: “In the immediate term, it feels less efficient being open. It feels like a tax because you’re like, ‘Oh God, another bloody opinion.’ And it slows you down, but it makes you more effective because, by collecting those opinions, you’re more likely to make a better decision that’s more considered. It’s actually an investment, not a tax. But it takes longer.”

Jay: “We have a very participatory culture. Which is a good thing! But then people feel compelled to participate in all the things – sometimes without knowing the context.”

Matt: “The reason people get flamed in comments [on an intranet page] is because you might write an internal blog post, and people respond however they want because they expect you to be open to all manner of feedback. And for a long time, we lacked a guiding principle on how to behave in that situation. So we talk a lot about ‘seek first to understand,’ and I think that was a response to people struggling to receive feedback. I think we still struggle with it. We are focused on sharing information openly, but not on how to behave when you’re on the receiving end of the share.”

Penny: “When I see people freaking out about an announcement or something, a lot of the time it seems they’re freaked out they didn’t find out about it earlier. And so, I feel like a solution to that is more openness rather than less. I know that’s not always practical and you can’t turn everything into a public vote, but… I mean, when I was working as a QA engineer, the worst scenarios were when I found out about a project too late to raise the risks and build safeguards into the project. And then I’d be the party pooper.

I think it’s gotten worse because the company is so big now and there are so many things going on that you don’t know about until they’re far along. It’s much easier to miss out pulling in a key group of people when you’re making decisions.”

Matt: “The best example that comes to mind is a couple of years ago when IT announced the bring your own device policy and it was widely hated at first. They collected feedback early on, but could have been more open about the potential differences.”

Denise: “The great thing about that episode, though, was that the people who wrote the blog, they also have to be open to the feedback that they’re getting back, right? So, they looked at the feedback they got and just went, ‘We can’t do this, we need to rejig it.’ And they did. That was that.”

Matt: “Yeah, the response was really good. But it was kind of a waste of their time up until that point. They’d done all this work and they had to throw it away. They didn’t understand the impact to their customers, and they got that feedback too late. So, as we scale, we have to re-learn when to share what.”

Jay: “I don’t necessarily agree that openness on its own slows us down. It’s the openness combined with people feeling compelled to participate. Think about some of our big decisions, like sunsetting a product. It’s really hard to be open in the course of making some decisions because you don’t want them being made by 3000 people. Even if you don’t have all of the data or context, you’ve got your own job to do. So, it’s like, trust that the people making the decision are gonna do a good job.”

Penny: “You can’t just live one value isolation. There’s a tension and a balance. Like how when you give feedback, you can be as open as you like, but you also need to not be a jerk. There are times when I know something, but it can’t be shared widely just yet for whatever reason. But you do want to inform some people because it will affect how they do their job. I find juggling those to be really uncomfortable.”

Matt: “I actually think that’s fine. I know that you’re open with me 90% of the time, and you know that I’m open with you 90% of the time. That builds trust for the times when I do need to keep something from you. So, oddly enough, I think the open culture helps us keep secrets better.”

Jay: “Even so, leading up to our IPO, there was no other choice than to make everyone in the company an insider. Otherwise, it would be such a shock to how we worked. Because remember, it’s not just financial information. We’d have to withhold material information about our products and our strategies from employees. It was a pretty bold risk to say we’re gonna walk the walk and inform employees in advance of a public disclosure. But there was just a unified belief that it would break the culture, or significantly disadvantage the culture and the way that we operated if we didn’t try to be as liberal with information as we possibly could. Because that’s how we’ve grown up, and it’s a strength.”

The journey to 5,000 employees (and beyond)

Penny: “I think what Jay said is especially true in that we have to keep building trust because having full openness into everything that’s happening and always wanting to have a say in everything that’s happening doesn’t scale.”

Denise: “There’s a difference between being open for debate versus open for informational purposes. Open for debate doesn’t scale. We can’t have 10,000 people arguing about a product or action, especially with how distributed we’ve become. But open for information? When you’re like, ‘This is what’s happening. Unfortunately, you don’t get to be involved in the decision, but smart people were, and this is the decision we’ve made.’ I think that does scale.”

Matt: “You have to be realistic, too. Years before we went public, we started restricting employees’ access to financial information for compliance reasons. I used to be able to see all the sales data in real time, but you can’t have that when you’re a public company. Like, no bullshit: we’re gonna have to keep some things closed. And that goes with trusting that what can be open will be open. I think the key to scaling is having no-bullshit honesty about what has to stay closed.”

Dom: “Open for me is more about the information I need to do my job. It’s things that affect me, – maybe even one click out that might affect me. Because there are a trillion Atlassian things that curious Dom would like to know about, but I don’t need to. And so, I think as we scale, the challenge is between the like and the need.”

Penny: “I disagree, actually. I think that getting information on a need-to-know basis is basically the opposite of being an open company. So, for me, being able to access the stuff that I like but am not on the critical path for is a key part of what makes us an open company.”

. . .

Learn more about what it means to live a culture of openness, including new research linking openness to team success.

Want more Open?

Join us for a special event exploring the future of work at Atlassian Open. We’re touring the world and making a stop in Vienna, Sydney, and Boston. Learn new ways to work Open, team trends, proven practices for better collaboration, and the important role cloud plays.