Joanne Thompson has a special relationship with the moon.

“I love to just look at it,” she says. “I even had a dream one time that I went to the moon. And you know when the moon looks just like a piece of mist up there? That’s how it was in my dream. I got there and I said, Where am I supposed to put my feet?”

Even though Joanne’s only been to the moon in her dreams, something she made has been there. Something that actually made traveling to the moon possible. Joanne, along with a team of seamstresses in the 1960s, sewed the spacesuits worn by the Apollo 11 astronauts. They worked as part of a team that included engineers and scientists on something where the stakes were literally life and death. It was the most difficult challenge these women had ever faced, and at a time when women were rarely heard or empowered.

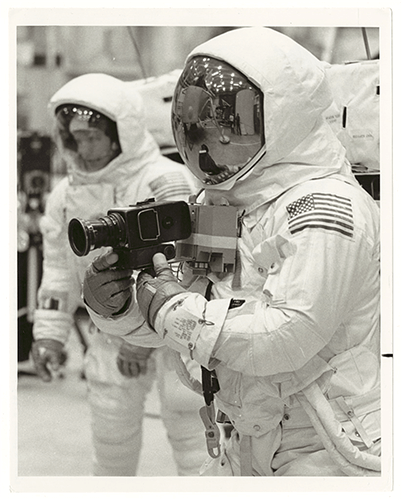

While most of us have seen the video of the moon landing, we rarely think about those big, white, puffy outfits the astronauts were wearing. Where did they come from? Who made them? How in the world did we know they’d be safe?

To find out, we have to go back a few years before the landing.

From girdles to zero-gravity

In 1966, a company named ILC (International Latex Corporation), based in Dover, Delaware, won a contract to make spacesuits for NASA’s Apollo program. You may have never heard of ILC, but you probably have heard of their biggest division at the time: Playtex. That’s right, the company known for flexible, comfortable bras and girdles was going to use that know-how to make garments for walking on the moon. To do that, they needed to build a team. And not just the scientists and engineers you’d expect, but a team that included dozens of seamstresses.

Joanne, who was already employed as a dressmaker, heard about the opportunity from a friend, took the required sewing test, and passed. “So I went back to my dress factory and gave them my notice,” she recalls. “In two weeks, I was working on a moon suit.”

Meanwhile, Jean Wilson was also a seamstress in Dover, and her older sister, who worked at Playtex, brought home news of the openings. Growing up in a family with 13 children, she learned to sew from an early age. “When I applied and they found out my credentials and my experience and everything else, they hired me. I think I was about 18.”

Neither she, nor Joanne, nor any of the women who applied had any experience in aerospace engineering. But they could sew the finest, straightest, tightest seams possible – over and over – which is exactly what NASA needed.

But regardless of how good they were, nothing prepared them for the kind of work they were about to do. “It was that type of a job where you had to go through training, learning how to read blueprints,” Jean remembers. “Everything was laid out for the way the suits had to be made. There was a lot involved.” And don’t forget, sewing something strong enough to withstand the vacuum of space was a challenge none of them had ever faced. Each seam had to have the right amount and type of stitches in order to bear the load.

Getting cross-functional on the factory floor

The seamstresses were only one part of the larger team. Because of all the rigor NASA required, a wide array of expertise had to be brought in, including many other folks new to the space industry: configuration management experts, quality management, and quality engineers.

According to Nicholas de Monchaux, author of “Spacesuit: Fashioning Apollo,” NASA knew instinctively to assemble a diverse team. “There were people who had no engineering training, but who were incredibly mechanically adept,” he says. Some of them had worked in the industrial section of Playtex, while others were sewing machine salesmen. They weren’t engineers, but they knew about manufacturing. “Then there was a group of engineers coming out of the University of Delaware. They were very well-trained, but also raw and young.”

And then, of course, were the seamstresses. None of them had worked with aerospace engineers, who, in turn, had never worked with garment makers. As Nicholas describes it, a typical scene would be a seamstress, a manufacturing expert, and an engineer sitting around a sewing machine. The seamstress would explain what the fabric could do. The manufacturer might explain what the stainless steel fitting could do. And engineer could then think about how it might all come together to meet the required tolerances or production processes.

Now picture, in that scene, 18-year-old Jean Wilson. “I moved up in a position where I was a lead sewer. So, I supervised several other women. Also, consider the color of my skin. I am an African-American, so at that time I was labeled ‘the colored girl.'”

We have to remember what things were like in 1960s America – having women in a highly technical workspace, providing feedback and input, was unheard of. In a society crippled with racism, chauvinism, and ageism, this team took diversity to another level. Not just diversity in expertise, but diversity in background and perspective.

The big advantage of such a diverse team was gaining access to expertise the engineers didn’t have, and didn’t even know they needed. The seamstresses knew from experience how a certain type of stitch or seam would hold up under stress. They knew what fabric could and couldn’t do. That knowledge was integrated into how each piece of the suit was designed so when it all came together, strength and integrity weren’t compromised.

“I can honestly say nobody I worked with on this, especially the engineers, would talk down to us or act like, oh, well, we’re just seamstresses,” says Joanne. Yet this was not a moment in history when women participated equally on teams with men. It was really an organizational victory, as much as a physical victory, creating the culture and systems that could allow this very different kind of manufacturing process to exist – especially within the ocean of paperwork everything in the space industry requires. Following procedure perfectly was not the mark of a job well done. Success was ensuring that every astronaut could survive on the moon.

Not because it is easy, but because it is hard

Although what they’re making is commonly called a spacesuit, it’s more like a self-contained space ship. As the only thing protecting the astronauts, it had to shield them from the elements, regulate their temperature, and provide air to breathe – all while allowing for free and easy movement.

It started with the astronauts being carefully measured. Then, patterns for all the different sections of the suits were created and cut out of the various fabrics by engineers. That’s when it was all passed over to the seamstresses to sew together. Each section would be x-rayed to look for any stray needles or pinpricks. The suits would then be tested by the astronauts, checking fit and functionality. If the suit passed all these levels, it was then copied a few times over for stress tests and as backups.

Neil Armstrong, Michael Collins, and Buzz Aldrin made numerous trips to be fitted, as Jean remembers. “They were like little kids at Christmas time. They were so excited to have become astronauts, and then to actually be to the point of putting on the suit they’d wear in space. It was almost like a bride-to-be getting fitted for her wedding gown.” (Almost.)

Despite the team spirit and the years of careful, meticulous work, there is one major worry during the final stages of the project: there was no lunar simulator that would let them test the suits in their intended environment.

The team had tested the suits every way they could, subjecting the fabrics to simulations of solar wind and moon dust, bouncing the suits around in high Gs on airplanes, even putting the suits in vacuum chambers. But what if the data NASA had about conditions on the moon wasn’t quite right? What if there was some other surprise waiting for them up there? No one would know until they stepped onto the moon. By then, of course, it will be too late to fix anything.

The moment of truth

Typically, Dover is silent and dark in the middle of the night. But in the early hours of July 21, 1969, hazy blue lights flickered in living rooms across town, across the county, and indeed around the world.

“When I saw him on the moon,” Joanne recalls, “it was hard for me to comprehend that those little parts I worked on, on the production floor, are now on the moon. It gave me goosebumps.” For her part, Jean remembers being so excited that she had made those suits that she found herself yelling and screaming at the television.

But excitement was only one part of it.

“I was afraid,” Joanne admits. “I was hoping there’d be no problems. It would have been hard to accept if something I did were to cause the whole program to fail, and possibly result in a man losing his life up there.” Given that the mission itself was the final systems test, nobody felt entirely relaxed.

The mission was a success, of course. The astronauts made it home safe and sound, as did the ten other astronauts who used the ILC spacesuits to walk on the moon over the next three years.

It’s been over fifty years since the moon landing and ILC is still around, still making suits for NASA. In fact, their recent spacesuits and prototypes influenced the xEMU, a spacesuit debuted late last year that will be worn by the first woman on the moon, intended to take place in a few years. The pioneering work of Jean, Joanne, and the rest of the team has taught today’s ILC team how to approach sewing in the context of life-critical applications.

So picture the moon landing. Picture Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin stepping out to walk on the moon. But the thing is, we’re not actually seeing Armstrong and Aldrin. In every image, we’re really looking at the work of Jean and Roberta and Joanne and so many others. Because what we see are the suits.