Regra de automação do Jira quando a solicitação pull é mesclada

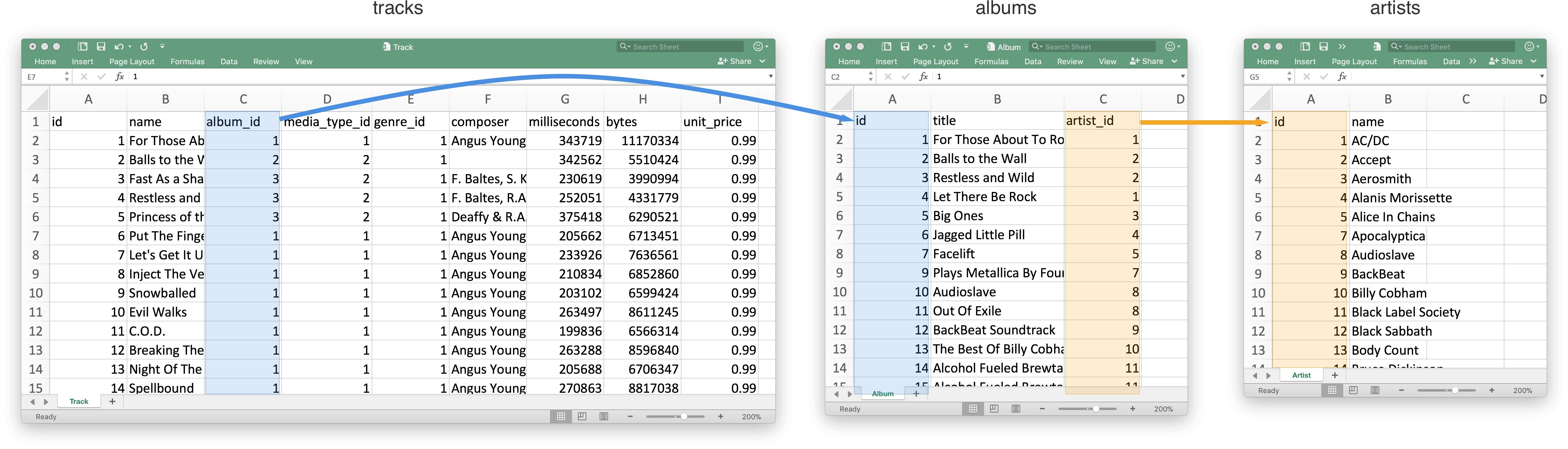

So far we’ve been working with each table separately, but as you may have guessed by the tables being named tracks, albums, and artists and some of the columns having names like album_id, it is possible to JOIN these tables together to fetch results from both!

There are a couple of key concepts to describe before we start JOINing data:

Indo além da agilidade

PostgreSQL is a Relational Database, which means it stores data in tables that can have relationships (connections) to other tables. Relationships are defined in each tables by connecting Foreign Keys from one table to a Primary Key in another.

The relationships for the 3 tables we’ve been using so far are visualized here:

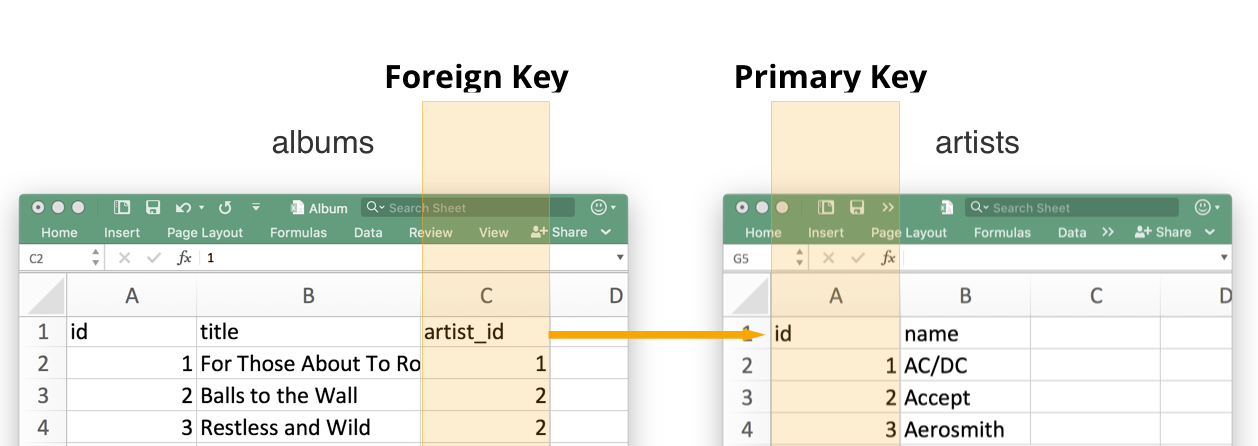

A primary key is a column (or sometimes set of columns) in a table that is a unique identifier for each row. It is very common for databases to have a column named id (short for identification number) as an enumerated Primary Key for each table.

It doesn’t have to be id. It can be email, username, or any other column as long as it can be counted on to uniquely identify that row of data in the table.

Indo além da agilidade

Foreign keys are columns in a table that specify a link to a primary key in another table. A great example of this is the artist_id column in the albums table. It contains a value of the id of the correct artist that produced that album.

Another example is the album_id in the tracks database. Earlier in this tutorial we looked up all the tracks with an album_id of 89. We also looked up which albums had an id of 89 and found that the tracks referred to the album “American Idiot”. TODO: Fix this paragraph/example.

It is very common for foreign key to be named in the format of [other table name]_id as album_id and artist_id are, but again it’s not required. The foreign key column could be of any type and link to any column in another table as long as that other column is a Primary Key uniquely identifying a single row.

Indo além da agilidade

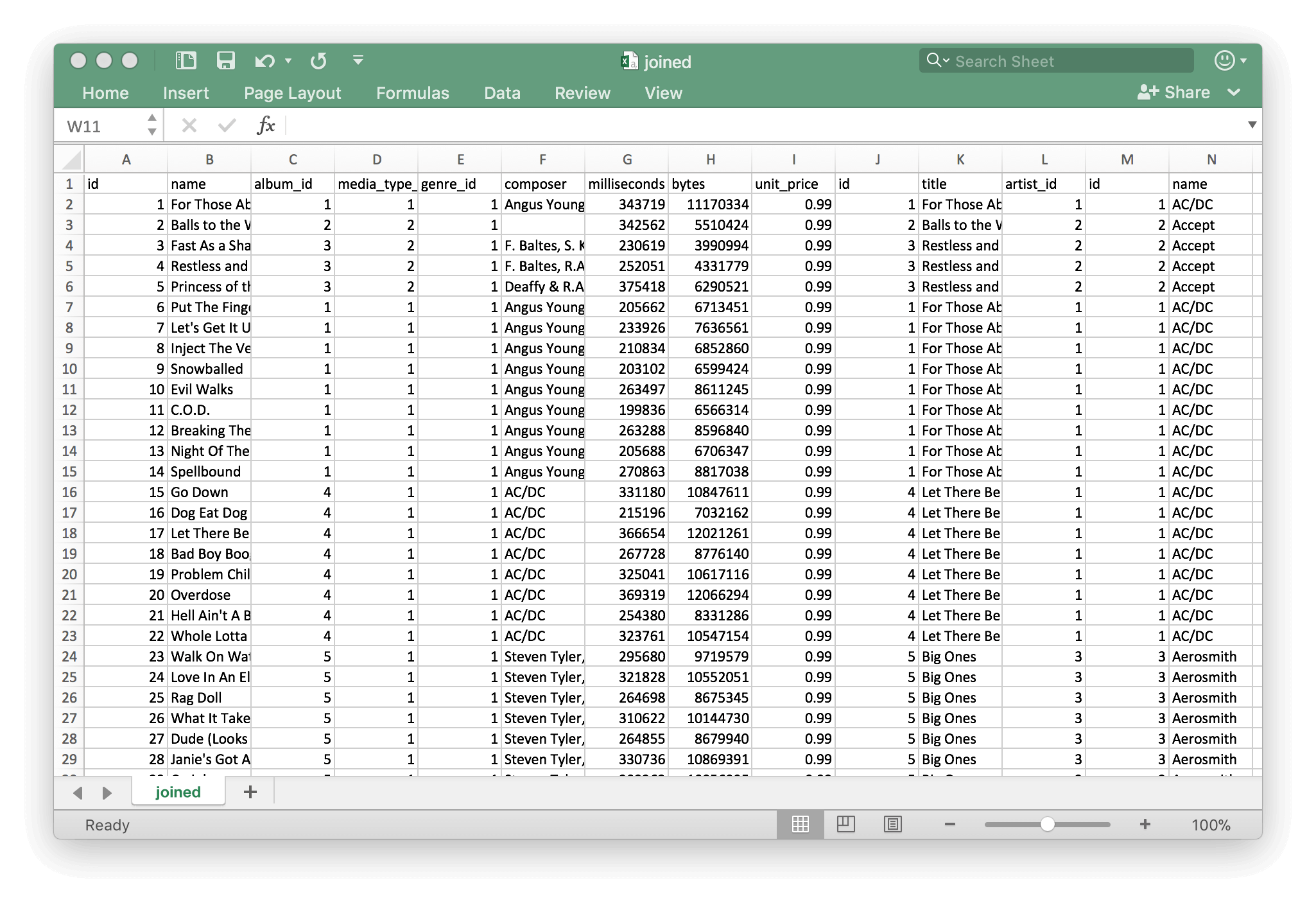

If we didn’t have relationships we’d have to keep all the data in one giant table like the one in the figure here.

Each track for example would have to hold all of the information on it’s album and on the artist. That’s a lot of duplicate data to store, and if a parameter in any of that changes, you’d have to update it in many different rows.

It gets messy already even for our small example, and just wouldn’t be realistic for real company implementation. The world (and data) works better with relationships.

Indo além da agilidade

So let’s get to it! To specify how we join two tables we use the following format

SELECT * FROM [table1] JOIN [table2] ON [table1.primary_key] = [table2.foreign_key];Note that the order of table1 and table2 and the keys really doesn’t matter.

Let’s join the artists and albums tables. In the above figure we can see that their relationship is defined by the artist_id in the albums table acting as a foreign key to the id column in the artists table. We can get the joined data from both tables by running the following query:

SELECT * FROM albums JOIN artists ON albums.artist_id = artists.id;We can even join all 3 tables together if we’d like using multiple JOIN commands

SELECT * FROM tracks JOIN albums ON tracks.album_id = albums.id

JOIN artists ON albums.artist_id = artists.id;Indo além da agilidade

There are a few different types of JOINs, each which specifies a different way for the database to handle data that doesn’t match the join condition. These Venn diagrams are a nice way of demonstrating what data is returned in these joins.

JOIN VISUAL | TYPE | DESCRIPTION |

|---|---|---|

|

| INNER | DEFAULT: returns only the rows where matches were found |

|

| LEFT OUTER | returns matches and all rows from the left listed table |

|

| RIGHT OUTER | returns matches and all rows from the right listed table |

|

| FULL OUTER | returns matches and all rows from both tables |

We can demonstrate each of these by doing a COUNT(*) and showing how many rows are in each dataset. First, the following query shows us how many columns are in the artists and albums tables.

SELECT '# of albums', COUNT(*) FROM albums UNION SELECT '# of artists',COUNT(*) FROM artists;And we know that each album does have an artist, but not all artists have an album in our database.

INNER JOIN

The inner join is going to fetch a list of all the albums tied to their artists. So we know that as long as each album does have an artist in the database (and it does) we’ll get back 347 rows of data as there are 347 albums in the database. And indeed, that is what we get back from the INNER JOIN:

SELECT count(*) FROM albums INNER JOIN artists ON albums.artist_id = artists.id;RIGHT OUTER JOIN

An OUTER JOIN is going to fetch all joined rows, and also any rows from the specified direction (RIGHT or LEFT) that didn’t have any connections. In our database, many artists don’t have an album stored. So if we do a RIGHT OUTER JOIN here which specifies that the right listed artists table is the target OUTER table we will get back all matches that we did from the INNER JOIN above AND all of the non matched rows from the artists table. And here we show we do:

SELECT count(*) FROM albums RIGHT OUTER JOIN artists ON albums.artist_id = artists.id;418 OUTER results minus 347 INNER results shows that there are 71 artists in the database that aren’t associated with one of our albums. Can you double check that that’s the case with SQL, by adding a WHERE condition to the above query filtering the results for those where there is no albums.id?

LEFT OUTER JOIN

If we chose to do a LEFT OUTER JOIN we’d be choosing the albums table as the OUTER target. And here we are verifying that there are no extra albums that don’t have an artist associated with them.

SELECT count(*) FROM albums LEFT OUTER JOIN artists ON albums.artist_id = artists.id;FULL OUTER JOIN

And finally a FULL OUTER JOIN is going to return the JOINed results and any non-matched rows from either of the tables. We know that in the case of this dataset those will only come from the artists table, and the result will be the same as our RIGHT OUTER JOIN above.

SELECT count(*) FROM albums FULL OUTER JOIN artists ON albums.artist_id = artists.id;Indo além da agilidade

We can do more than one JOIN in a query so let’s bring tracks, albums and artists together and see how it looks. Try running the following which is LIMITed to just 5 rows, as it’s a large result set and we don’t need to see all of it.

SELECT * FROM tracks

JOIN albums ON tracks.album_id = albums.id

JOIN artists ON albums.artist_id = artists.id

LIMIT 5;Scrolling right you can see that there are a lot of columns as the result has all of the columns of each joined set. You can also see that there’s a conflict as there are 2 columns title name. One is from the tracks table and one is from the artists table and the result set isn’t handling that properly. It’s just using the names from the artists table in both columns!

We can fix this by using aliases. In the following we’re trying to get the names of 8 tracks along with the name of the artist. Run it and you’ll see for yourself. Can you fix the mixup in them both having the same column name using the aliases AS "Track" and AS "Artist".

SELECT tracks.name, artists.name FROM tracks

JOIN albums ON tracks.album_id = albums.id

JOIN artists ON albums.artist_id = artists.id

LIMIT 8;You have now unlocked the knowledge to fully enjoy most of the double entendres in this amazing song about Relationships. Do take a moment to enjoy.